A memoir about identity, tracing the roots of my adoption and meeting my birth family

I was adopted. I am an “adoptee”. For most of my life I didn’t really care. The word had no meaning. I never thought that discovering my origins might help me overcome my existential crisis, or that my emotional pain had more to do with being adopted, than being part of the human condition I never thought the past had any connection with the future. For me, adoption was a non-issue.

Call it denial. It didn’t seem to matter that I didn’t know who my mother was, or my father…grandmother, grandfather, ancient ones… These shadowy ancestors remained in the category of “spirit guides.” After all, I was rescued from the void. I have a family who loves me. Even if we aren’t related.

I have no memories of kids being cruel, or calling me “illegitimate” or “bastard.” They certainly didn’t call me “pre-nuptial,” in those days.

OK.

Maybe the way in which I discovered I was adopted could have been more sensitive. Disclosure is always difficult. No one in my family remembers the incident except me. Maybe my memory has distorted the truth, even though the “discovery” was more monumental for me that anyone else.

I was nine when my younger sister blurted out “well, I’m theirs’ and you aren’t…” Excuse me? I dragged my mother into the kitchen for proof. She would confirm my identity. But no. It was true, I was adopted. “So, who am I now?” She said, “You were chosen.”

I finally understood the meaning behind those words. In a strange way I felt relieved. If I had lost my identity, I would simply invent another. Destiny became a conscious act. If no one could tell me the origins of my birth, then perhaps I wasn’t born. I was magical.

My parents insisted “no,” I was no different than my sister. Except that she was “born” and I was “chosen.” Never mind, we were both loved. We went back to living as if nothing unusual had happened, as if I had been born to them. I bought into the myth that love can replace lost ancestors. I was not “different,” and adopted families did not have problems distinct from biological ones.

At least that’s what I thought until I began reading books on adoption. Now my life reads like a case study for “adoptee psychology.” It turns out my rebellious nature, chronic depression and low self-esteem are all a result of being adopted.

Apparently, my entire family is in denial, although it’s not entirely their fault. Social workers told them that if they treated me the same as a biological child that environment would overcome heredity and I would just disappear into their home. No one thought that the secrecy surrounding traditional adoption would create any psychological problems.

We all want to believe that love conquers all. Mostly it does, except that the blood tie is essential to the human psyche and the child who grows up without it is someone who has lost the thread of family history.

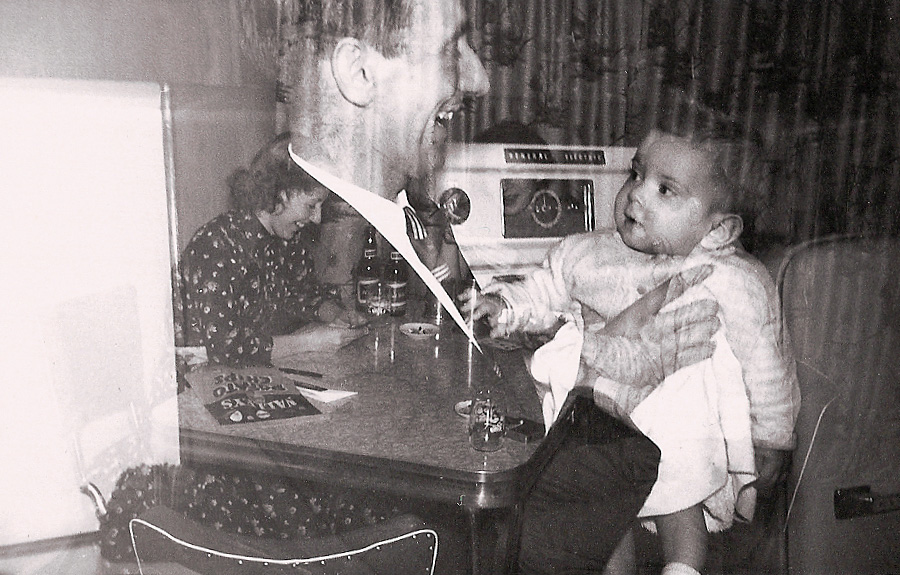

I was adopted in 1957, one of 1373 babies adopted in Alberta that year. My parents-to-be were recent immigrants to Canada from the UK. They decided on adoption after having difficulty beginning a family.

My mother shares her experience, “I had lots of bad luck when I was pregnant. I had a full-term which was stillborn. And I went six months and the baby was less then 2 lbs. And then I went three months and had a miscarriage….It wasn’t too nice….So when we came to Canada we decided we would put in for adoption.”

Adoption occurs out of loss. The birth mother loses her child, the child is severed from its genetic roots, and the adoptive parents lose the child they couldn’t have. I rescued my adoptive parents from childlessness. In return they treated me as if they had given birth to me. My father says, “When I was a kid every family had about eight or ten kids, not like it is now when people make a conscious decision not to have any kids—nobody did that. You needed children. You needed them as much a they needed you.”

There are no rituals to mourn the loss of an unborn child, broken dreams and disconnected families. In this way, the closed adoption system brings with it the need for denial. My mother says, “It was distressing. Nobody ever talked about it. These days they seem to have groups for everything….Then, they just said ‘You’ll get over it.”

Adoptive parents are expected to be happy (and most are), adoptees are expected to be thankful (and most are), and birth parents are expected to forget (and most do). While my birth mother was trying to forget her loss, my adoptive parents were elated to receive the phone call that they finally had a child. Such is the emotional trajectory that gets played out in the adoption game.

“They phoned and said there was a baby at the hospital,” says my mother. “She was small so we couldn’t have her right away. So, I went to the hospital to have a look and she was lovely….She was in an incubator, because she was 4 lbs., 10 oz. She was beautiful…so little….“They let her out earlier than they said they should because I think they got fed up me visiting.”

My mother describes me: “She was alert, wide-eyed. She was beautiful…She was a gorgeous baby. Small, dainty… she settled in great.”

My father remembers differently: “She cried like hell quite an awful lot. I don’t think she liked to be put down, I think she liked to be held.”

I wanted to be held. Forever.

I wonder if being separated from my birth mother left a primal wound? Did the events in the nine months between conception and birth mold my personality? Sometimes I think I was fully conscious in utero, a love child who overheard my father tell my mother he didn’t want me. And the conversation with the doctor when she made inquiries to abort me. Did I shift in her belly in protest? Did this mysterious uterine world inflict its disturbing emotions on my psyche? Was I born premature because I wanted to escape her body as it convulsed in anguish, pain, and despair at the thought of giving me away? I lay in an incubator alone for seventeen days, a piece of myself disappeared. This sense of incompleteness wasn’t filled even when I was placed in the open arms of my adoptive mother. Did I miss the scent of my “other” mother, the sound of her voice? Could this be the root of my fear of rejection, loss and abandonment?

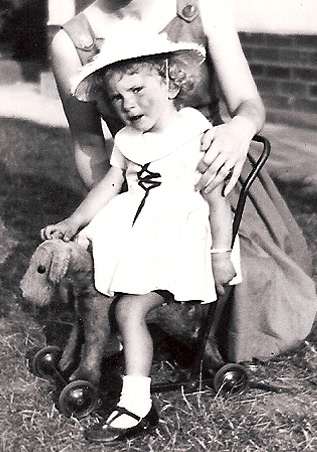

My parents gave birth to my sister when I was three. I don’t recall anxiety around this event. I never felt less privileged than her. They did everything to make me feel loved and part of the family. And they still do. My emotional pain is not because my parents didn’t love me enough—it is a result of the closed adoption system that makes all triad members participate in a conspiracy of silence.

In the sixties, when adoptive parents bought into the “as if born” myth it was even more burdensome because all along they pretended their child was no different. Now they had to burst the bubble and confess that this was not true. In denying the reality of a difference between the adoptive child and the biological child, adoptive parents might think they are confirming their love for the adoptee, but in fact they are denying the adoptee’s reality.

The “as if born” script was perplexing to most adoptees because there was a subtle subtext that the adoptive parents would love and nurture him if he acted “as if” he were not born to other parents. In other words, if he disavowed reality—which means giving up a part of himself.]

“We told her she was chosen when she was about 8 years old,” says my mother. “It was easy, really….We never ever used ‘adoption.’ We just said you were ‘chosen’ and that was it.”

My father remembers, “They intimated it would be wise from the get go to introduce her as our ‘chosen daughter’ and that is what we did. I don’t know when she found out. She probably never found out…she never came and had a heart to heart talk. She just settled in and became what she was—a member of the family.”

My mother remembers, “My mother came to visit from Scotland and one night we were sitting at dinner and Heather said, “Gran, did you know I was chosen?” She looked at me and I think was surprised that we had discussed it and at that age she knew she was adopted. The conversation went on for about five minutes and then that was it—forgotten—just to let her know, in case she didn’t know…”

I lived in a world of mixed messages where I was being treated like the chosen one, yet denied my difference at the same time.

“They have never been treated differently,” says my father. “As far I was concerned my first daughter was my daughter and that is all there was to it.”

In denying any difference between myself and my sister, my parents thought they were confirming their love for me, but it sometimes felt like they were negating my reality.

“It is kind of funny,” recalls my mother, “the two children who lived up the street were “chosen” and Heather was “chosen,” and my other daughter came home one day in tears and after we got it all straightened out, she couldn’t figure out why she wasn’t ‘chosen,’ because the three of them had been telling her how special they were, and that was it. So, she wasn’t special.”

When I read adoption memoirs I discovered that all adoptees have their “chosen baby” story. Call me a greenhorn, but I really thought mine was special. Suddenly, the words were robbed of their power. The first time I remember hearing those words was when I was eighteen and my father had come to visit me in Montreal. We were having a heart to heart where we spoke of my adoption for the first time. He told me always to remember that I was special because I was chosen. Those words comforted me for years.

Although I had been referred to as the “chosen daughter,” I didn’t understand that meant I was adopted until much later.

For adoptees, life does not begin at conception, nor at birth. My life began the moment I discovered I was adopted. “ I am theirs’ and you aren’t, ” says my sister. Disclosure is the birth of consciousness, the realization of being different from people around me.

“ I am theirs’ and you aren’t. ” Those words obliterate my sense of self. I will never be the same. My mind splits—one part welcomes this unprecedented flight to freedom, to reinvent myself, but the other goes underground to suppress my real feelings of loss and grief. I put my pain into a black box and give it to Pandora for safe keeping. I descend into the void. I disappear into my private darkness. Adolescence is an unbearable turmoil of depression.

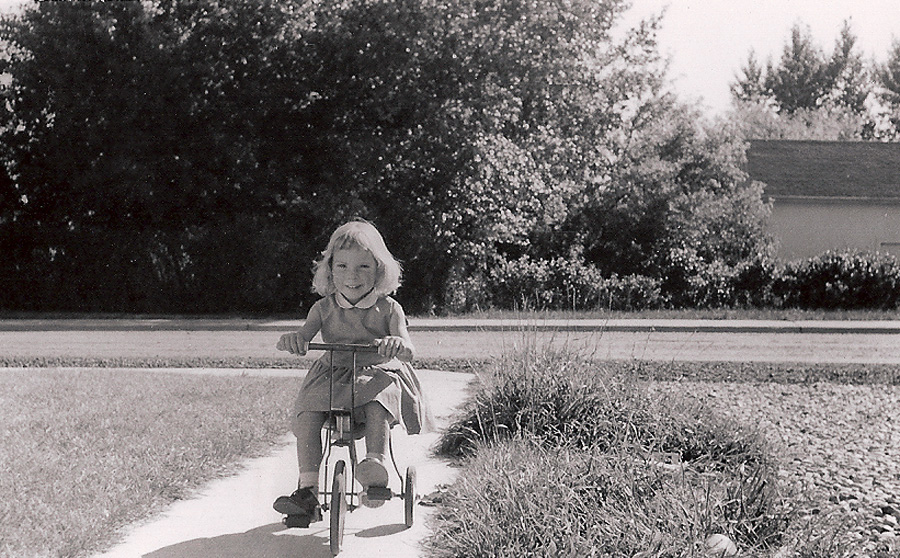

Psychological literature claims that adoptees experience more than the usual amount of inner angst at adolescence because of the unanswered questions that plague us. I was reading Hesse, Camus, Sartre, Anais Nin, and the Beats. I was in pursuit of the meaning of life. Identity became the big issue.

The sense of self originates in the body. At puberty, when your physical shape shifts and there is no one who looks like you, a question like “Who am I now?” can have ominous overtones. My adoptive parents were unprepared to deal with my conflicted emotional state. Suddenly, years of suppressed anger that no one expected me to have, emerged in a form of silent, contemptuous disregard for my mother. Was this hostility displaced anger towards my birth mother?

My mother says, “I just see her as my daughter who is moody at times.”

I was angry that I was adopted; angry that I was different and that no one knew what that felt like; angry that I felt powerless to find out the truth of my origins; angry that I could not express my real feelings in an atmosphere of denial. And, hormones to boot. Some adoptees confront adoption openly and integrate it into their concept of self. I avoided the issue.

“We talked a lot as a family,” says my mother. “It was just conversation. It wasn’t a big dealie….If she was annoyed she never said she wished she had been somewhere else.”

Author and psychologist Betty Jean Lifton believes that the blood tie is fundamental to the human psyche, and without it, the adoptee is programmed for a difficult future. The severing of the individual from his of her origins lies at the heart of the psychology of the adopted child. According to Lifton, the adolescent adoptee forms two selves—the Good Adoptee and the Bad Adoptee—to survive inside the closed adoption system built around the notion of “untruth.”

The Good Adoptee makes believe that she wasn’t adopted and conforms out of fear of rejection to become an “absolute people pleaser” so it won’t happen again. The Bad Adoptee goes underground to seek authentication in fantasy, or in rebellious behaviour because she can’t tolerate her lack of connection in the world. The Bad Adoptee “acts out” the belief that the reason she was given away was because she must have been “no good.” By taking on the imagined behaviour of unworthy birth parents—from criminal to whore—the child forces the adoptive parents to prove their love, (again), or abandon her to the “tough love” system.

Co-existing within my psyche was both the responsible child who didn’t want to hurt my adoptive parents, and the Outlaw who refused to sacrifice my intregity. I identified with the Bad Adoptee—the Rebel. The Outsider. I started my own teenage rebellion. Sex, drugs. Rock ‘n roll. True to the Bad Adoptee, I lit fires, lied, stole, smashed up the family car and did drugs. I went to great lengths to demonstrate that I was different. But then what hip young teen wasn’t rebellious in the late sixties?

At 13, I took LSD, MDA, mescaline, cocaine, peyote, mushrooms, hashish, marijuana, ecstasy in pursuit of higher consciousness. Alcohol and drugs numbed feelings of loss and grief. Sometimes I wished I were dead.

B.J.L. says that the Bad Adoptee “takes on the dress, mannerisms and lives of rejected people or groups.” I took on the fashion of my beatnik brethren. At fourteen, I wore faded jeans with triangular flares, hiking boots and a Woods ski jacket. My mother thought I was a disgrace. “You used to be so beautiful…” she would tell me. By grade 12, my hippie days were behind me and my fashion victim days upon me. My dark brown Mary Quant lipstick, and brown suede platform boots from Kings Road in London, glam-rocked the bourgeois corridors at Western Canada High. The sorority girls thought I was “gross.” My sister was in one. She stopped talking to me.

“I didn’t realize she was as rebellious as she tells me she was,” my mother says. “Ignorance is bliss.”

“Maybe in the higher teens,” says my father. I never looked at it as being rebellious. Of course a teenager can be argumentative, or go through phases of this, that or the other. But I never look back and say you were a rebellious little devil. She may have been.”

Not being biologically connected to others gave me the freedom to experiment. I felt as if the boundaries of my white middle class existence were closing in on me. My spirit was in danger of being crushed. I went further underground to blow apart the narrow-minded views that excluded marginalized people—bohemians, hippies, freaks, artists, punks, queers—who somehow were more like me, than not.

I was self-destructive and did antisocial things as a protest, as a cry of pain. I was sullen and withdrawn at home; flamboyant and thoughtful with my friends. Fortunately, my adoptive family didn’t abandon me. Just this side of total family breakdown I discovered a much safer arena in which to “act out”—drama class—where I could try on different roles, characters, personalities. I could search for my identity. Theatre provided me with the opportunity to do the psychological work necessary before I was ready to search for beginnings. That would have to wait.

While the process of untangling my emotional past had begun, but I spent another decade submerged in sleep, struggling with fears of abandonment, loss of trust, low self-esteem, depression and anger. Separated from family and friends, at times feelings of disconnectedness and loneliness were overwhelming. There were days I couldn’t leave the apartment for fear that people might look at me; their eyes penetrating to the core of my being. I was an impostor. My heightened sense of awareness crashed into deep depression. I turned my back on anti-depressants, even though I had terrifying images of disintegration and nothingness, of my alienated spirit spiraling towards darkness.

I sought refuge in theatre class and began to construct my own narrative. My prophet was the passionate French visionary, Antonin Artaud. He embodied the modernist notion of the suffering, misunderstood artist. I felt his pain when he described his soul being murdered by shock therapy. I admired his journey to Mexico in 1936 where he visited the Tarahumara Indians to participate in their peyote rituals. When science was god, Artaud was ahead of his time looking backwards into the soul—into chaos. I would follow in his footsteps and trek to the ends of the earth for self discovery—enlightenment.

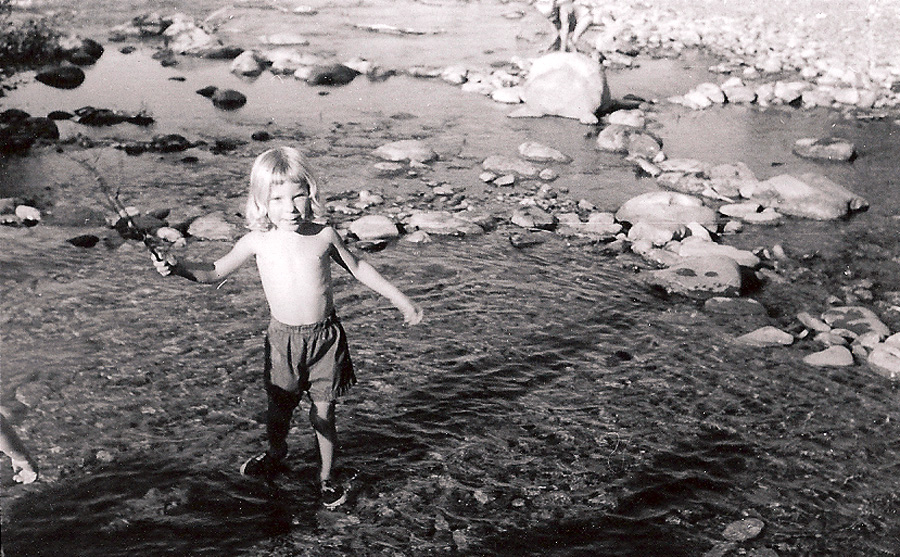

I hunt for meaning on the edge of continents, in tropical rain forests and across frozen glaciers. I search for my ancestry in Western Europe, No Man’s Land and behind the Iron Curtain. I travel La Ruta Maya and sit atop pyramids in Tikal, at dawn, overlooking the jungle canopy in search of my spirit guides. I push my body to extremes in an attempt to break through the invisible shield that separates me from life, and tour the Canadian Rockies leaving fleeting evidence of my existence in fresh tracks through powder snow. I do all this without my adoption records, without the key to my origins, because I want to know who I really am first. I want to trust my intuition.

Eventually I had to come back down into the forest, into the dark psychological wood where as a child I ran terrified escaping from a witch, until my untamed hair tangled in the trees. I had to stop running and face my fears. Adoptees release emotional pain by numbing, therapy, or the journey back to self. I had embarked on the quest but I was still not ready to search for my origins.

I had fallen in love with a sensitive and flamboyant man who possessed a brilliant, penetrating mind. We were intimates, born in the same hospital, in the same year, three months apart, and we lived less than a mile from where we were born. He awoke a part of me that was ready to take flight.

One day he was working in the library of the hospital where we were born when he saw a big black book titled BIRTHS: 1957. Without hesitation, he looked himself up. Then, he found my entry. There was the name of my birth mother and the name she had given me.

What’s in a name? An identity. Sydney Margaret Coe. My birth name contains my birth father’s first name and my birth mother’s name. It is a beautiful name with resonance and meaning. I tell my adoptive parents of my discovery and they give me my adoption papers—the original adoption order and a letter issuing my new birth certificate.

My original birth certificate was stamped “illegitimate” and sealed away. Forever. I was issued a new one that substituted my adoptive name for my birth name. What happens when a name is erased from memory? Denial is at the heart of existence.

Imagine what is it like to be forbidden by law to know the woman who gave birth to you? To see her face, to hear her voice, to touch her skin, to know her name. No one can imagine it because it is unimaginable.

Even though I knew her name it still took me another decade to make contact.

In October 1993 I wrote Alberta Family and Social Services to request information about my biological background. I received “non-identifying information” on my birth parents compiled at the time of my adoption. I registered with the Post Adoption Registry.

Unlike adoptees who spend years immersed in secret fantasies about their birth parents, I never once imagined who mine might be. No, I never went there. I traveled to Prague once on a whim I might be Slavic, and into sweatlodges in search of Native ancestors, but I never tried to envision the actual people. Now I didn’t need to, my birth parents came to life off the page.

I read my “social history” as if it contains the key to my identity. “History of the Adoptive Child—Father” and “History of the Adoptive Child—Mother.” I am holding the paper. It says I am a second-generation Caucasian Canadian—a mix of English, Scottish, German and New Zealand ancestry.

It says here that my birth mother was 25 when she gave birth to me. Today, she would be 61. Is she still alive? Is she married? She too has “a round face, clear complexion, hazel eyes, a dimple on her chin.” What does she look like now? She is described as “an intelligent and articulate person” with a “stylish appearance.” Will I recognize myself in her?

Like me, she has a sister three years younger.

It says here my birth father is a widower. “Blond, 6’1”, 185 lbs, well-built.” He looks like my partner. “Handsome and well-groomed.” It seems that I have acquired his personality—“a sociable individual who could be moody at times.” My friends laugh when I tell them that, as if the words perfectly describe me. Is “moody” a polite way to say he is alcoholic? Abusive? Is this why my mother didn’t marry him? It says he was aware my birth mother was pregnant and provided financial assistance. Is he wealthy?

Both of them have a university education. D oes this explain my intellectual side? No one in my adoptive family went to university. I am impressed she did, in the fifties.

I like the idea of my grandfather as a “master mariner,” exploring the high seas. Does this explain my sense of adventure? My desire to be soothed by the constant rhythm of the ocean?

An interesting detail stands out. “Our reports indicate that you were the first child born to your birth mother; however she did have a son, born in 1958, who was also adopted in Alberta.” I have a brother out there somewhere.

Two months later I receive a letter from Alberta Family and Social Services asking me to contact them about an important matter. My biological brother had registered with the Post Adoption Registry years earlier and the social worker wants to know if I would meet him. My brother remembers the day he received the news.

My brother remembers, “That was a neat day. I was at school. I had a phone call from my wife, and she was really excited, saying the social worker had phoned saying I had a sister and asked if I had any problems meeting her and I said “None whatsoever, bring it on.”

It’s winter. My partner drives me through the Albertan landscape to the small rural town where my brother lives. Guess whose coming to dinner? As the reality of meeting my destiny sinks in, my adventurous spirit leaves my body. The closer I get the more anxious I become. The thought of looking into his eyes fills me with terror and dread. Will my constructed identity will be obliterated by his gaze? I look out the window at the trees lining both sides of the double-laned highway. I am in a tunnel re-entering the birth canal hurtling towards the womb. I am nauseous. What if I don’t like him?

We stop at an intersection. The psychological crossroads, between knowing and not knowing, where I either retreat or make an aggressive move forward. I am determined to drag my imagined self into reality. When I meet this blood brother will I lose my special status of “not being born,” and become mortal, like everyone else. In the process of becoming human will I lose myself ? It feels like a sacrifice; a slaughter.

“I wasn’t nervous,” says my brother. I was excited and happy. It is an exciting thing….I knew immediately that she was my sister. I could tell by her face. I think we hugged…..It was a week night and we stayed up late talking. She had some pictures and I brought out my family album…so we discussed past life until 2 a.m.”

My brother is a male me. I am attracted to the double. I dig my volunteer fireman-high school teacher-eco/solar architect-musician-and father-of-two, brother. If I ever need to be rescued by the jaws of life I want him to do it. I feel safe in the house my brother built. My young niece cuddles her pet hedgehog. I am her. The moment when the identity question is answered, when I know he is my brother, occurs when he reads me his favourite poem by Leonard Cohen. I have listened to Leonard Cohen since I was fourteen. My brother has a poetic soul. I feel so positive about our reunion that I tell him I will track down our “natural” mother. It will be my gift to him.

In February 1994, I join the Triad Society for Truth in Adoption in Canada, a non-profit organization dedicated to search and support for adult adoptees, birth parents and adoptive parents. I send them my documentation and birth mother’s name. A search consultant faxes me the address of my birth mother in forty minutes. It is their “fastest search on record”—because I know her name, and because she hasn’t moved from her childhood home which is still registered in the name of her father, to the Master Mariner. She is waiting to be found.

At this stage of the search some adoptees are so excited they just pick up the phone or show up on her doorstep. I decided to respect her privacy and give her a chance to respond in her own way. I spent two months writing the perfect letter. I say that I am not angry, that I have a good life, that I have no expectations. I simply want to meet her, once, to ask a few questions about my social and medical history. I send it and my baby photo by “registered” mail.

The decision to search is a moment of choosing myself. I write the letter to my birth mother and am struck by the realization that this act will change my life forever. There will be no going back.

There are many reasons adoptees don’t search. Some fear rejection, or are afraid of upsetting their adoptive parents, of disturbing the birth mother, some are afraid of change, others are afraid of losing whatever identity they have. Our mythology is filled with stories about those who are punished for daring to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge. For most of my life, I felt I should respect her decision to relinquish, until I realized she was under the influence of Victorian morality. “What is past is past.” “Let sleeping dogs lie,” hushed voices whisper. “You’ll open up a can of worms.”

The decision to give up a child for adoption must be the most difficult thing a woman can do. Usually it occurs from lack of financial and emotional support, and from social and personal pressures the young mother cannot endure. In the 1950s, most unwed mothers were sent to institutions where they bore their children in shame and secrecy.

My birth mother says, “It was a big shock and I didn’t believe it. And you don’t know who to go to. Fortunately Syd did have some friends who were quite close to him and they told me what to do. They were of course thinking of an abortion. I went to one place and saw the doctor and the place and left and never returned. So there was no alternative other than to have a child.

“Fortunately, the father suggested that I stay in a hotel he owned. I knew the people who were running the hotel. Because I didn’t show, I was able to ski and do these things and so life went on pretty normally. And it was the days of the sack dress, too, fortunately. It wasn’t too bad at all. So, I came home and I don’t think anyone knew. Maybe some did, but it was never said.”

What must it have been like for a birth mother to keep her pregnancy a secret, move away from her family, and then give birth to her baby, alone?

She says, “I was pretty shaky. Really shaky…to the point of throwing up. I have always been able to put things out of my mind. I mean I have to. So, I am not a callous person. I just simply had to do what I had to do. I had no counseling. I had no choice but to get on with it and I knew if I dwelled on it I would have no life.”

Nurses prevented mothers from holding their newborn saying it made relinquishment more difficult. “Pretend it never happened,” they whispered. And so, powerless within the closed adoption system, the mother keeps the most important and traumatic event in her life a secret—her first baby gone in a relinquishment as irrevocable as death.

“I remember them putting the baby on my stomach and it was sort of grayish, says my birth mother. “And then I went to see her once after through the glass, because I did feel that if I had held her that I would never have been able to give her up. I was always worried about whether I could give this child up, but then common sense took over. I knew what I had to do and I was going to do it.”

When a child dies, the mother is surrounded by family and friends who mourn with her, but when she loses her child through adoption she bears her suffering in silence.

My birth mother remembers, “Someone came up to me and said, ‘How are you?’ And I just burst into tears. I felt so foolish. Anyway, one of my friend’s husband was there who was a lot older that I was and he said, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ And I said, ‘Nothing.’ And he said, ‘Something has happened to you are you are really feeling sorry for yourself, smarten up.’ And I did. It was exactly what I needed. It sounds harsh. But he was dead right.”

All birth mothers have a real need to know that their child is well and was raised in an atmosphere of love.

My birth mother says, “It was a great sense of relief to know all was well. She had a good life and was treated very well, and educated well, and has turned out to be a brilliant person. So, for that I am thankful.”

Within days of sending my registered letter my birth mother phoned me. “As soon as I saw the letter I knew what it was,” she says. “Excellent letter. I read it and fortunately I was home alone. My sister did not even know anything about this. So, I phoned Heather right away.

The phone rings. The instant I hear her voice I know who it is. It reminds me of my own. She talks for a long time, but I can’t hear her anymore. I know she is talking. I try to hear her words but they are separating. I cling to the velvet smooth texture of each word, but the meaning is lost in the sensation of sound. My birth mother remembers, “…we had quite a long talk. I think I was nervous and probably shaky. She asked about her father and I said he was dead. I think I told her a little bit about him, and my family and that she did have three half sisters. She told me quite a bit about herself.”

Out of the sound blur she tells me my father is dead. Now, I hear the words.

“He was murdered by the Satan’s Angels bike gang,” says my birth mother. I hear those words as if they are inside a bell jar, they echo inside my head and the rest of the conversation tinkles against the glass, unheard. Silence sounds like thunder. Who was this generous and flamboyant man whose intoxicated dreams led him on a walk on the wild side to his death?

“He was murdered by the Satan’s Angels bike gang.” Bludgeoned to death. I want to throw up. His murder takes on the symbolic force of my own darkness: the violent thoughts, fear, depression. Like some child prodigy following their genetic code to greatness, do I have a bad seed inside me that will lead to my destruction? Like him, will I die a violent death?

I am guilty. I have no entitlement to these thoughts. No right to grieve his death because I never knew him. But, his death has been psychically imprinted upon me. The Stoney Indians say that when a father dies his spirit goes into the youngest daughter. That is me. I am haunted.

“He was murdered by the Satan’s Angels bike gang.” Suddenly, my life falls to pieces. My relationship of twelve years is over. The original rejection trauma returns, as do the critical voices. I’m fatally flawed and destined to be alone. I am an empty shell. All that remains is my skin. I go underground, inside the black box, and imagine eagle talons, jaguar claws ripping myself apart so I can be reborn. With owl eyes, I learn to see through the darkness.

I research his murder. I read newspaper clippings and court transcripts—a testimony by a 17-year-old girl who witnessed his death. I have to visualize the brutality to release my own fear. I no longer believe I’m going to die violently. In healing myself, I heal the spirit of my murdered father.

The return of the adoptee, the chosen one, lost one, can disrupt the birth mother. Mine had to break her silence of 38 years and tell her sister about my existence.

My birth mother says, “We were watching some ice skating on television and my sister called me and said come and watch this Canadian pair. It was the World Championships in Tokyo and she said, ‘Look at this girl, she is an unwed mother.’ And, I said, ‘Well, speaking of unwed mothers…’ and I blurted it out. Well, I think her mouth just fell open. And she started to cry and then laugh. We both just didn’t know what to do.”

My aunt says, “I took it very calmly, but I also was thrilled and thought of how wonderful it is to have some other people in our family because we have no close relations other than cousins who are alive. This would be a treat actually, but I also had a terrible feeling of what she must have felt having lived through all those years with this secret that hardly a soul that she was able to tell. And not being able to tell her family, I think, would be the worst thing.”

Adoptive parents can have anxiety over the arrival of the birth mother. Some feel threatened, betrayed and deeply hurt. They fear it might cause them to lose their child. I sent my parents a letter to assure them that this momentous occasion would in no way sabotage our love, or the fact that I considered them to be my real parents.

My father says, “Great! She said ‘you will always be my parents, but I would like to find out.’ I thought she would say that. How could you receive all that affection all those years, and give it back, and then because you found this person who is your biological mother, say I am going to forget all that now? It is impossible to write that off.”

My mother says, “I didn’t mind in the least. I thought it was great….She wrote us a lovely letter and said that no matter what happened we would always be her parents and that she respected us and loved us. I didn’t feel badly. Perhaps if it had happened when she was 14 it might have been different, but at this stage I’m content with things as they are. I know who she is. She is not a possession. It’s up to her to do what she thinks is right.”

My birth mother and aunt live in their childhood home. It is comfortable house with an understated cream-coloured elegance, accented by exotic objects from distant cultures, of woolen carpets thrown hastily onto hardwood floors. It is a treasure trove of family history. Threadbare Victorian teddy bears are stuffed into empty birdcages. China dolls with soft bodies wear rumpled lace smocks and tiny leather boots. Clothes from every decade threaten to burst from over-stuffed closets. Dislodged photo albums, overturned jewelry boxes, and long-forgotten relics lie discarded, swell out of boxes and drawers too small for memories.

On the mantelpiece is a photo of the master mariner aboard his three-masted ship. There is a photo of my grandmother who travelled alone in 1914 by steamship from New Zealand to Victoria to marry him. A great aunt sits on a camel in Egypt alongside some handsome sheik. Lawrence of Arabia.

There is a photograph of my birth mother and me the day we met. In it, we wear animal brooches—me a faux ivoire whale and her a silver dog—that are the same size, pinned in the same location, above the heart.

My aunt describes the experience of seeing me for the first time:

My aunt says, “I couldn’t take my eyes off her because she bore such a resemblance to my sister. Not especially the way she looks now, but as I have known her through the years. There was so much that was like her, could have been another one of her…knowing she was related to me, and my sister’s daughter, I was simply enchanted and excited.”

My birth mother says, “She was very much like me as a young person. That was quite exciting. You look at a picture and see yourself. So, I knew what she looked like….Quite often you would see someone on a street that may have some sort of resemblance to your family…I think if I had seen her I would have known.”

My birth mother responded to my return in a similar way as she dealt with the original situation. She wants to keep my existence a secret—except to a few close friends. Old taboos still linger.

My birth mother says, “I think it was the times…if it had of been today no one would have blinked an eyelash. But they certainly did then. It still hangs on. I guess it is fear of what people will think. But why should one really care what one would think? But one does if you are of this vintage. I find that most difficult. I just think that a lot of my parents friends are still alive, elderly, but lucid and I think a lot of them would be really shocked. Whether or not I should care if they were shocked I don’t know, but I suppose after I always tried to please people I really don’t want them to know. After all, my mother didn’t know so why should they know?

“As for the others, it is a private thing for me because it had to be private for 38 years. So, it is very hard to talk about and then you get afraid that if it does get out, and you have told some of your friends, others will be hurt that they don’t know, but this isn’t intentional. The funny thing is everybody I have told has been thrilled. It is quite fun really.”

I remind her that I’m not a secret. I’m a person.

In March 1996, I arrive at the Phoenix airport where I am to meet one of my birth father’s daughters, my biological sister. In the confusion I miss her and look for someone who looks like me.

My blood sister says, “So we went and waited and waited, and when we went to check with information we discovered she was coming in at another terminal. And, of course, at this point, I knew her plane had landed. She’s probably standing around. When we got there people were flowing out of the terminal. And how am I possibly going to know this person? And I happened to turn to my left for some reason, and I just knew it was her. There she was standing. There was a great familiarity about her. I could recognize the features. It was a very strange feeling to recognize somebody without ever having met them.”

Later, I meet my two other half-sisters, each totally different. At a birthday dinner for my Buddhist/Ayurvedic healer sister, one of her two handsome sons, my nephew—one with a new baby who I guess is my grand-nephew—tells me that I look like his mother, that I have her exact eyebrows.

My other sister, an AA survivor who plays pool and likes C&W bars, has a wicked sense of humour.

The reunion is a joyous occasion and we do not feel like strangers. But even though I am important to them, I cannot expect them to feel as close to me as they do to one another. Suddenly, I have gone from living in a nuclear family of four, with no extended family in Canada, to having twenty-eight blood relatives. And there are more out there.

Once the euphoria of the initial meeting wears off most adoptees experience a post-reunion depression when reality sets in and you have to navigate a mutually acceptable relationship with an “intimate stranger.” Usually, there is an intense first meeting, followed up by one or two brief meetings, occasional phone calls, an exchange of e-mail, and birthday cards. My brother reflects on how the events have changed his life.

“It was neat to meet a blood person, no question,” says my brother. “It felt good. She was an interesting person. If she wasn’t, I might not have pursued it. You never know what the person is going to be like. Maybe its someone you don’t want to hang with, who is not interesting. But she was, so I made subsequent visits.

“But, I don’t have any expectations. I am prepared for a non-continuation…if it is not meant to be I am prepared for that just because I am busy. It is like friendship—some continue, some fall by the wayside. It’s not anyone’s fault, it’s just evolution…We don’t see a lot of each other. We have our lives, but I will think to phone her.

“I just don’t have a lot of time. I’m a bit anti-social. I’m not excited by family reunions….A difference in my life? I don’t think so, not to belittle it. I’ve enjoyed it and it’s a very healthy thing to do. But it hasn’t made a difference in my life, really. I like her and it’s neat to know I have a mother, because before I didn’t. But I don’t have any real desire to spend a lot more time with anyone that I am. The meetings I have, the dinners, that happen naturally—I don’t crave any more…It’s neat to have someone to phone on mother’s day and I do that. I’m not trying to be insensitive. I’m just busy. I have a family and a job. I’m not looking to be mothered.”

My aunt says, “I think it has made it richer, given our life another whole dimension. I don’t feel that either me, or my sister, will die without having anyone to leave all our things too. It is nice to think that there is someone there who might be interested in some of the family memories.”

My birth mother says, “…It is something else to talk about with those of my friends who do know, but other than that it has not changed life as such because you get set in your ways and have commitments.”

I am committed to these relationships for life.

A wild synchronistic event occurs one day. I show some adoption photographs to a friend—he recognizes his father in one of them. It turns out that his father and my birth father were good pals, much like we are, one generation later. Last summer, he was vacationing with his family at the same lake where my birth father and his father used to hang in their youth. During our visit I am taken to see the stylish house my birth father built on the lake. The one I am so familiar with from the photographs.

I tour the elegant ‘50s bungalow made of wood and glass. It’s like being inside a dream, walking though a still photograph. Is this possible? Two years ago he was a character in a photograph who I got to know through details of his death. Today, I am standing in his bedroom, the room where I was conceived. I feel his presence and am overwhelmed that my journey has led me here. To the beginning.

I look out the window to the lake where the gentle water laps the shore. There, at the end of the dock is the legendary Sheppard boat that he shipped out west from Ontario. Is it a mirage? I walk along the wooden dock, a fragile border betwixt sky and water, that holds back the ghost world from reality. I enter the mystic. I slide into the boat, into the exact leather seat where he sits in my photograph, cocktail in hand, laughing.

I have finally come home, even though it isn’t my house and he is no longer here. Last time we were in this place, together, I didn’t exist. Now, I exist and it is he who is insubstantial. We have exchanged places. I leave him in his boat to dance in the chimera of light on water. I walk back towards the house and transform this spirit world into reality. It is the end of the road. The end.

“All in the Family.” The story of my adoption told in a creative non-fiction style that blends two voices – factual history and personal memoir – in a psychological narrative that chronicles events in my adopted life from the moment of discovery to the reunion with my birth family, as well as the journey towards “self.”

CBC Ideas. June 1998. © Heather Elton

One Comment

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hello Heather,

Thank you for sharing your story. This line: “It turns out my rebellious nature, chronic depression and low self-esteem are all a result of being adopted,” jumped off the page at me. So THAT’s why, I thought.

My father also was killed when I was quite young. My mother remarried to a man who seemed threatened by the existence of someone before him. I was not allowed to talk about my origins or discuss it in any way. I grew up not knowing I had aunts, uncles and cousins, even though I had met one of them. The door was shut.

Last time I saw you, which would have been in the late eighties, I think, I was still something of a mess.

Much later in life I did some research on my father’s family. I am the keeper of the photographs and correspondence that showed he existed. I approached my aunts, uncle and cousins and found a level of acceptance I could not have wished for – and a closing of the relationship with my stepfather, mother and half-sister, who deny my existence to my niece and nephews. Still, I’m glad I chose this path. I know who I am.

Last year I changed my name to include my father’s name – the name on my birth certificate – in my given names. At some point I intend to drop my stepfather’s name.