W A T E R

Shiva’s liquid energy flows in the form of the Ganga

Just before dawn we slip into a small wooden boat and float out on the mighty Ganga. It’s so pleasurable, gently drifting across the water as the city awakens. I can see why devout Hindus refer to Varanasi as ‘Kashi’ – the Luminous One, the City of Light. In the Kashi Kanda (26.27), Shiva resides on the three high peaks that encompass Varanasi (his three-pronged weapon, the Trishul) and spreads light all around the city. Bliss and light are one. I get a taste of luminosity as the morning sun spreads across the river and strikes the high-banked face of this city, turning the ghats rose.

Varanasi, India

Varanasi, India

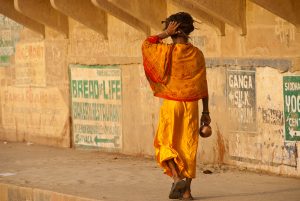

The river is broad and there is nothing built on the opposite bank – just a wide sandy beach receding into the distance and then a line of trees. 20,000 Hindus a day bathe in the river to purify their sins. Everyone comes here to perform morning ablutions. Young Brahmin priests dressed in traditional red lungis wash out puja bowls on the banks of the Ganga. People sit in silent mediation; others delight in storytelling. Somewhere bells are ringing. Women wash clothes while wet ones dry in the sun; meters of brightly coloured saris stretch across the ghats. Buffalo lounge in the water. There are endless scenes of the tenderness of elders helping each other to dress, hippies smoking chillums in conversation with India mystics, wandering widows, wandering bulls, and holy Sadhu ascetics (Sanyasi) sitting on the colossal flights of stone steps leading down to the water’s edge.

Varanasi, India

Varanasi, India

Of the 84 ghats that line the curve of the Ganges, five of them are considered most sacred as they represent the bodily parts of Lord Shiva. I try to visualize the supine form of the Shiva with his head at Assi Ghat, chest at Dashaswamedh, navel at Manikarnika, thighs at Panchganga and feet at Adi Keshav, but it is too vast. The idea of the navel representing the fire element, and the place of both the charnel grounds at Manikarnika and the site tantric heat necessary to transcend to the spirit realm draws me deeper. I can imagine the Vedic horse sacrifices performed by Hindus on Dashaswamedh Ghat in 2 BCE, and horrific images of fresh blood seeping into the Ganga, and wonder what the contemporary version is today and why sacrifice really is necessary, feeling a surge of distain for religion but let the aversion pass, erase the stain of momentary perception, and come back to the present moment and my breath. I feel like a character inside a film. Drifting past the ghats is like watching the history of India unfold before my eyes – the post-Vedic world dissolves into the medieval period of Muslim invaders and the imperious Raj Kingdoms, to the East India Company (1764), India Independence (15th August 1947), and into the modern world. I’m really overcome by the grandeur of the Mother Ganga, the myriad temple spires, and the Mughal-style sandstone pavilions, the palaces at water’s edge, and the seamless life on the ancient ghats. Many seem to be falling down, but the decay only adds a patina of authenticity. Time stands still, and I’m suspended in some dream-like sensation of floating through the city of Gods.

Varanasi, India

Varanasi, India

Ganga, Varanasi, India

I feel as if I could simply disappear into this City of Light, dissolve into the liquid form of Shiva – the crescent shape of the Ganga. I feel a great sense of peace that comes with deep understanding. Yet, as I look into the muddy brown water it doesn’t take long before my intellect drags me back to more mundane view and I wonder if a burned limb will float by and just how filthy is this holy water that purifies sins? I light a small votive floating candle and send it off adrift in the water, precariously on a leaf, along with my prayers to embrace moksha. The pink rays of dawn colour the water rose. A couple years back in Delhi, a Vedic astrologer did a reading for me and ominously said the only way I could tone down the strong transits of Pluto that continuously plague me was to find a rusty nail ring from Varanasi. I spot the perfect nail in the boat and when I mention this to Umesh he says he’ll take care of it. Melodic chanting floats in the air. Instead of hearing some traditional Indian bhajans, the voice carried across the Ganga this morning belongs to none other than the American devotional singer Krishna Das! I get a good chuckle over the irony of this, but realise it’s a sign of the sacred and mundane merging. Varanasi is part of the global economy, Krishna Das is a kirtan master, has spend time in India and his records sales probably surpass those of Ravi Shankar.

Varanasi, India

Well before we get to Manikarnika burning ghat, the smoke and ash from the funeral pyres clouds the landscape. It’s a magnet drawing us towards its center – the navel. It’s impressive with 750 stairs backing up from the Ganga to the Old City, with ancient temples and wooden buildings turned black from centuries of smoke. Out of this obscurity glow the fires and the silhouettes of people moving around inside the cremation grounds. Towering above is the ominous red Tarakeshvara, the most important temple on the ghat because it holds the form of Shiva who imparts the liberating Taraka mantra, the ‘prayer of the crossing,’ at the moment of death. Sri Rama Jaya Rama Jaya Jaya Rama. Lord Shiva whispers the mantra into the ear of the deceased to ensure moksha (liberation) from worldly life. ‘Sri’ means Shakti or Sita. ‘Ra’ symbolises the fire that burns our karma. ‘Ma’ represents water – the peace that surpasses all understanding. ‘Jaya’ means victory to the spirit over the flesh.

Nuria is looking ashen-faced as she stares at the burning pyres, smoldering fires, and men in white gazing on as the body of one of their relative crackles and dissolves in the flames. Overhead the ever-present vultures circle patiently. Children play in the ashes, cows wander through, goats balance on piles of wood, feral dogs sleep in the warmth of the ashes or scavenge for remains. Bodies swathed in bright colours lie waiting for the next pyre. Workers constantly tend the pyres to keep them burning. Jutting from the stacked logs, I can make out a human limb, or head, of one of the departed. The endless cycle of life and death stabs me in my belly as I contemplate samsara.

Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, India

Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, India

I remember my first true understanding of death. I was about 11 years old, sitting in our old Studebaker car outside a shopping mall in Calgary with my father when he told me that he wanted to be cremated when he died. I felt physically sick at the thought of losing him, yet decades later when he finally passed and I felt honoured to be with him in his final days, sending him love and sweetly soothing him, in a way that it remains my most cherished and sacred spiritual experiences. I spread his ashes into the five elements high in the Canadian Rockies – into the sky, wind, earth, and torrential waterfall to echo the sound of water for eternity. Fire carried my prayers for a good rebirth or eternal peace. Even here, through the seeming horror of it all, the scene is somehow peaceful and uninterrupted. Perhaps Shiva really is personally delivering the deceased to Nirvana, or else people have come to embody and accept the reality that everyone we ever know will eventually die, including our self and that this is not necessarily a sad thing, rather a cause for celebration at living a good life.

Our boat docks at Manikarnika Ghat. The cremation grounds got its name because of its proximity to Varanasi’s most sacred pool, the Manikarnika Kund. Also known as Chakrapusharini, or Discus Lotus-Pond, it is the world’s first pool and tirtha. According to the Kashi Kanda, Vishnu carved this beautiful lotus pool with his discus (chakra) and filled it up with his sweat. His work completed, Vishnu sat nearby for eons performing fierce austerities. Shiva apparently was so impressed with Vishnu’s devotion that he shook with delight and lost his jeweled earring – Manikarnika – in the pond. Each year when the Ganga recedes, alluvial silt is left in the tank but then refills, miraculously, in time for Shivaratrei (Shiva’s birthday). I climb down the perfectly symmetrical stone-stepped sides to the pond and feel the exceptionally silky water from the Ganges. A Brahmin man smiles at me, his hands in Namaskar, and I feel a beautiful connection as his divine being greets my divine essence, and again I feel drawn deeper into the sacred city.

Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, India

Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, India

Beside the tank is the small Adi Kesava temple, which has a set of Vishnu’s marble footprints, also known as Charanapaduka. Vishnu apparently stood in meditation here for about 500,000 years to please Shiva. I have a small silver charm of Vishnu’s feet on my pendant and the priest blesses it with a red puja mark. I feel a genuine surge of true devotion, perhaps because Vishnu’s feet have been part of my life for many years. ‘Om vande gurunam caranaravinde’ is how the Astanga yoga chant (an excerpt from the epic poem the Yoga Taravali) begins and I’ve said it over 10,000 times. It makes reference to bowing to the feet of the guru, the feet of Vishnu, ultimately your own Inner Guru, which is where the yoga journey leads. This is the first of the 108 shrines on the famous Panchakroshi pilgrimage route and I appreciate that Umesh has chosen to bring us to this temple first.

Om Namo Narayana.

Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, India

Manikarnika Ghat, Varanasi, India

We disappear into a labyrinth of meandering narrow serpentine alleys of the Old City. Shafts of light penetrate through the darkness, illuminating the mysticism. The backstreets are drenched in the fragrance of incense and puja flowers. Snake charmers, Murti carvers, dreadlocked hippies, pilgrims, mutilated beggars, spiritual wannabes and saffron-clad sadhus haunt the streets lined with ornately carved doorways and exquisite decaying houses. Umesh leads us to the epicenter of Shiva’s city, the Vishvanath Temple (or Golden Temple) that was partially destroyed by the Muslim rulers who built a mosque on the site. There are armed soldiers on the streets guarding both the mosque and the temple, and only Hindus are allowed inside. We must be satisfied with a glimpse through a crack in the wall and I can see the gold gilded roof. A feeling of resentment arises I’m not allowed into temples, which usually are run by fundamentalist Shaivite groups. It turns out that an exact replica has been built at the University of Benares and we get visit it. I turn my back on religion, spirituality intact, and get lost in the maze of lanes that always return to the Ganga.

Varanasi, India

Varanasi, India

Varanasi, India

Snake Charmer, Varanasi, India

Murthi, Varanasi, India

We end a brilliant morning with a delicious South Indian breakfast of idly and masala dosa, made by a street vendor outside the South Indian ghat. It’s as fresh and tasty as any in Mysore. Exhausted, we collapse into one of Varanasi’s oldest chai shops and watch the world unfold around us.

South Indian breakfast, Varanasi, India

Chai, Varanasi, India

Continued in Part Three: Fire >

Heather Elton is a yogini, writer and photographer living in London.