IN THE MORNING OF TIME, IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF SATYA YUGA, when the mountains and plains and forests of the world were newborn, there was a lake – the most beautiful lake the world would ever know. It sparkled like liquid gold. Into it poured the clearest streams from the glaciers of the Himalayas. Its surface mirrored the sky. Every day as the sun rose and set it blushed the colour of roseate coral. At midday it turned the thundering blue of lapis lazuli. And at night the stars set themselves in the surface like glittering diamonds. The lake was at one with the heavens, a vessel of wealth and tranquility upon the earth.

There were many strange and beautiful spirits in the lake, and their watery domain was governed by the snake gods known as Nagas. Crowned with precious jewels in their heads, the Nagas guarded the fabulous riches of the lake. Foremost among the Nagas were King Kartok and his beautiful queen. The lake became know as Nagahrada – the Lake of the Nagas.

As the aeons passed, the lake also drew to its shores siddhas, accomplished sages, who meditated upon the waters from the surrounding hilltops. The first such sage to arrive at the lake was Vipashvin, the first of the seven historical Buddhas – the first human being to attain enlightenment.

As Vipashvin sat high atop Nagarjun Mountain, the eyes half closed, hands resting lightly on his thighs, contemplating the sacred nature of water before him, a lotus seed miraculously appeared and hung suspended in the air before him. Softly, like a moth, Vipashin spread his right hand so that the seed might drift down on his palm.

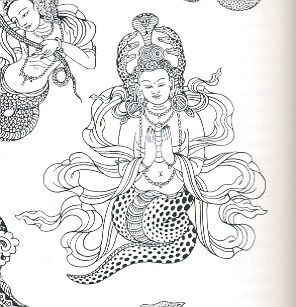

Right, A Buddhist drawing of a Naga. Nagas are mythical semidivine beings considered to be the underworld guardians of treasures and concealed teachings, and they can manifest in serpent, half-serpent, or human form.

Cover page, Manjushri is depicted as a male bodhisattva wielding a flaming sword in his right hand, representing the realization of transcendent wisdom which cuts down ignorance and duality. The text supported by the lotus held in his left hand is a Prajñaparamita Sutra, representing his attainment of ultimate realization from the blossoming of wisdom.

Then in his wisdom, Vipashvin knew what he must do. He closed the seed in his fist and raised himself to his feet and circumambulated the lake three times/ and he threw the lotus seed high into the air so that it spun in a rainbow arc out into the middle of the water where it landed with an almost imperceptible splash. He recited charms over it, and a wondrous prediction came to him, and he began to chant: ‘When this lotus shall flower, the primordial Buddha, Swayambhu, the Self-Existent One, shall be revealed as a flame.’ And in his mindfulness he also predicted that in a forthcoming era a great bodhisattva called Manjushri – He of Great Majesty’ – would come from China and he would drain the water in the lake, thereby leaving a fertile valley fit for human habitation.

“THE FLOWER WAS WONDROUS TO BEHOLD. IT HAD TEN THOUSAND PETALS WITH DIAMONDS SPARKLING ON THEIR UPPER SIDES, PEARLS SHIMMERING BENEATH THEM, AND RUBIES GLEAMING; THE SEED LOBES WERE EMERALD, AND THE STAMINS LAPIS LAZULI. A GIGANTIC FLAME OF SUCH BRILLIANCE IT TRANSFORMED ALL THOSE WHO SAW IT.”

And so, over the years, the seed drifted down into the silt at the bottom of the lake and in the era of the second historical Buddha, Shikhin, it began to germinate. The lotus seed had taken root at the site of an eternal spring, source of the Goddess herself, hidden deep in the earth. It was the secret opening, the womb, from which all life began, a hidden source of the Goddess know as Guhyeshvari – ‘Mistress of the Secret.’

Drawing thus upon the source of all things, the lotus sent its stem steadily upward from the pitha, the seat, of Guhyeshvari through the murky depths to the clear waters above where, reaching the air and sunlight at last, it burst into a flower as large as the wheel of a chariot.

Left, Kali Yantra; the essence is the triangle. Manjushri prepared a suitable conduit for the Goddess’s emissions and concealed the goddess behind a triangular stone slab. In the center of the stone was a hole through which the water could safely issue forth.

The flower was wondrous to behold. It had ten thousand petals with diamonds sparkling on their upper sides, pearls shimmering beneath them, and rubies gleaming, in their centers. The pollen of the flower was golden; the seed lobes were emerald, and the stamens lapis lazuli. From the center of the flower radiation a gigantic flame one cubit high and of such brilliance it transformed all those who saw it. The flame itself was the Adi Buddha ‘Swayambhu’ Jyotirupa – the Primordial Buddha Self-Originated Light-Form – and its light consisted of rays of five colours, white, blue, yellow, read and green, which were the essence of the five Transcendent Buddhas who personify the five knowledge’s of a fully enlightened being.

In time, the third Buddha, Vishvabhu, came with his disciples to pay homage to the sacred flame of Swayambhu in the great lake of serpents, and he stood on Mount Phulchok to take darshan of the primordial light, and offered his puja in the form of a hundred thousand flowers. And in the presence of his disciples he confirmed that the time had almost come when the great bodhisattva, sweet-voiced Manjushri, would come.

Above, Tantic depiction of Goddess with mala of skulls, curved knife and skull bowl of nectar (amrit). A metaphor for killing pride and self-cherishing. Right, Mandala of Vajrayahari yogin inside the sacred triangles.

Indeed, at the very time, in faraway China, on the five-peaked mountain of Wu-tai Shan, the bodhisattva Manjushri, entered into a deep mediation and became aware of the existence of the primordial Adi Buddha in the form of a flame on the other side of the Himalayas in the lake know as ‘The Abode of Serpents.

MANJUSHRI TOOK UPON HIMSELF HUMAN FORM AND LEFT CHINA TO TAKE DARSHAN OF THIS PLACE, carrying in his left hand the book of the wisdom and in his right a shining sword called Chandrahas (Moon Derider).

As soon as the bodhisattva came upon the great lake of serpents he circled it three times leaving soft indentations with his feet in the surface of the water. Then he made a circuit of the holy mountain around the lake. Taking each peak in one stride, his silken robes fluttering like prayer flags, he went first to Mount Najarjun; and then to the peak of Mount Pulchok; and then he strode on to Mount Champadevi; and finally, alighting on the peak of Sengu which rose like an island in the middle of the lake, he paid homage to the sacred flame of Swayambhu.

“MANJUSHRI RAISED HIS SHINING SWORD ABOVE HIS HEAD AND BROUGHT IT DOWN CLEAVING THE VALLEY IN TWO, DRAINING THE LAKE TO EXPOSE THE FLAME OF SWAYAMBHU.”

And as Manjushri gazed upon the lake stretching in all directions, it occurred to him that men could venerate the primordial flame more easily if the lake was drained. So he decided to expose the flame of Swayambhu and all the sacred locations that were underwater and entered into a deep meditation on how best to do this. And when he had seen how he could do it, he summoned all his strength and with a mighty roar raised his shining sword above his head and brought it down upon Kotval Mountain, cleaving it in two. Then he slashed further clefts at Chobar, Gokarna and Aryaghat and the water began gushing out, crashing in silvery cascades towards India.

The Nagas, great snake kings, realising that their precious home was being destroyed, came to Manjushri in despair. Manjushri told them he wished them no harm and was sorry that, for the greater good of men and all sentient beings, it had been necessary for him to drain the lake, and he implored the Nagas not to leave the Valley but to take up residence in a special pond he would create for them; and he assured them that they would receive worship from humankind forever. Manjushri knew that the Nagas were auspicious beings who knew the secrets of rain and wealth and other things that would be of great assistance to the future inhabitants of this land.

The Nagas acquiesced and slithered into their new home in Taudah pond. Here the great Karkotak, kind of the Nagas, constructed a magnificent underwater durbar, and Karkotak’s queen sat on a throne studded with jewels, shaded with three umbrellas of white diamonds one above the other. And though, in years to come, men tried to drain this pond in order to find this durbar and steal its treasures, none has succeeded. The pond of Taudah is where Karkotak and his beautiful queen dwell to this day.

Above, Detail of the devotional torana at the Sanku Vajrayogini Temple. Photos: Heather Elton

WHEN AT LAST THE GREAT LAKE HAD DISAPPEARED, MANJUSHRI RECEIVED DARSHAN OF THE SWAYAMBHU. Adi Buddha on the full moon of the month of Karttika and for the first time the mysterious root-sources of the thousand-petalled lotus that had once laid at the bottom of the lake became visible. The site was wondrous to behold. The lotus seed, with its three corners deep inside the earth, had lodged around a deep, dark opening in the shape of a triangle, like the entrance of the female sex. The site reeked of liquor and foamed with the froth of lowers and incense. This was the yoni of Guhyeshvari, the Goddess’s lower mouth, her sex, and the essence of her being.

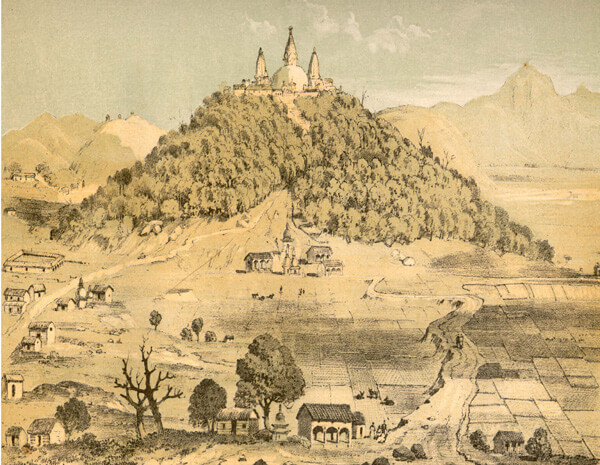

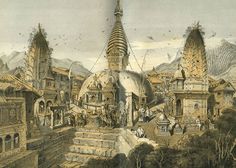

Left, Historic drawing of Swayambhu and its vicinity by Daniel Wright. (From History of Nepal, translated from the Parbatiya by Munshi Shew Shunker Singh and Pandit Shri Gunanand: with an introductory sketch of the country and people of Nepal. Daniel Wright, M.A., M.D., (Editor) Published by University Press, Cambridge, 1877.

But now a whirlpool was beginning to rise at this spot and, fearing that it might fill the entire valley with water again, Manjushri took in one hand a mighty diamond thunderbolt called a vajra and began to mediate deeply on what he had seen. He visualized the luminous form of the Goddess, seeing it in the form of water, visible everywhere, and as he achieved this visualization, he rejoiced and worshipped it with deepest reverence and thus restrained the up surging torrent.

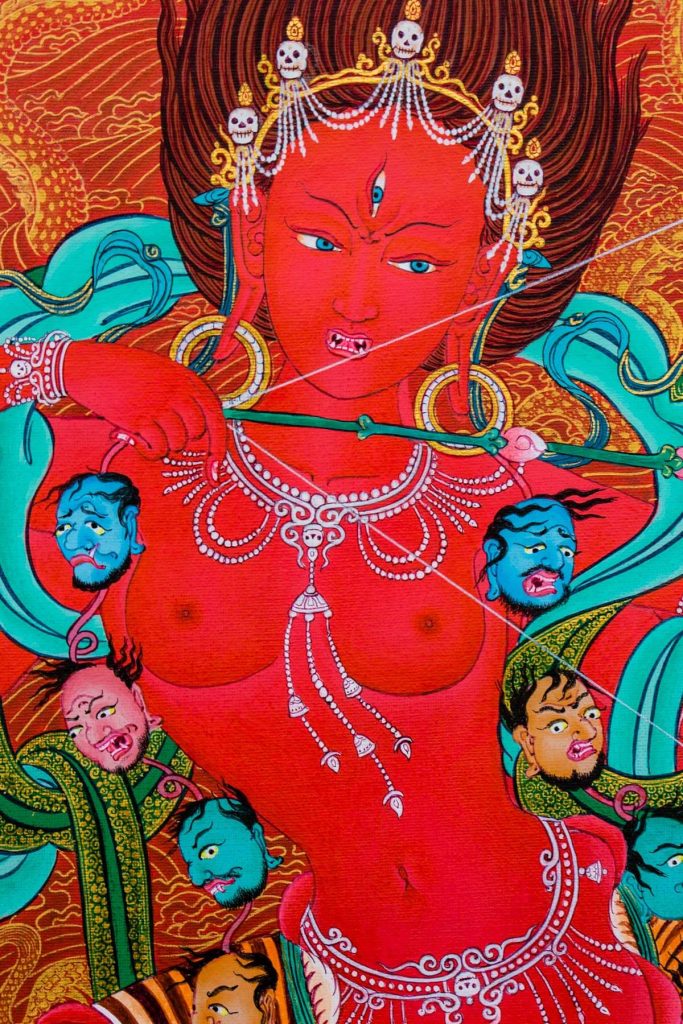

Right, Kurukulla yogini. “Kurukulla is yet another form of Vajrayogini, one that especially magnetizes passion and transforms it into wisdom. Like Vajrayogini she is depicted as red and blazing with flames, in dancing posture, holding in her hands the emblematic hooked knife and skull-cup of amrita, together representing the union of bliss and emptiness. Her ornaments of bone and jewels are similar to Vajrayogini’s, but she does not hold the khatvanga trident staff. In additional hands she draws a flower-bedecked bow set with an arrow and holds other weapons that indicate her unique identity.

She shoots her victims with the arrow in order to infect them with passion, thereby subduing discursive thought; with the hook in her lower right hand she draws the practitioner close; the lasso in her lower left hand trusses the practitioner’s passion, transforming it into wisdom. She dances on the corpse of the self, signifying her selfless activity.” ~ “Dakini’s Warm Breath,” pg. 146, by Judith Simmer

First, she revealed herself to him as a young girl, sixteen years of age, with round breasts and firm thighs, naked but for her beauteous adornments… Suddenly she had two thousand arms, each wielding a weapon of destruction more fearsome that the next. The constellations orbited in her hair; her earrings were wailing ghosts. As she danced, surrounded by a whirling chorus of skeleton devotees, waves of vibrations rippled through the universe. Fearlessly, she trampled upon the mighty forms of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, beating them to her will with the pounding of her feet.

So pleased was the Goddess with Manjushri’s devotion and his recognition of her hidden source that she gave darshan to him in her universal form. First, she revealed herself to him in peaceful aspect, as a young girl, sixteen years of age, with round breasts and firm thigh, naked but for her beauteous adornments, dancing with her face towards the north. On her head she bore a magnificent crown of the Five Buddhas; her earrings were the sun and the moon. She had three eyes, lovely as lotus petals; and

she played entrancingly with a cleaver and a skullcup in her hands. As she danced, her girdle of bone and garland of human heads around her neck swung hypnotically to the rhythm of her body.

Left, Troma Nagmo, Tibetan Buddhist Kali. Closeup from a painting of Machig Labdron. 19th century.

Then as Manjushri gazed in wonderment, the apparition of the Goddess began to change. Her eyes became the sun and moon; her third eye, a non-ending fire. Intoxicated with the five forbidden nectars and dressed in a tiger’s pelt with garlands like lightning flashes, the Goddess began to dance. Blasts of heat and searing cold began to emanate from her body.

Suddenly she had a thousand faces. Two thousand arms fanned out from her sides, each wielding a weapon or instrument of destruction more fearsome that the next. The constellations orbited in her hair; her earrings were wailing ghosts. As she danced, surrounded by a whirling chorus of skeleton devotees, waves of vibrations rippled through the universe. Fearlessly she trampled upon the mighty forms of the great gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, beating them to her will with the pounding of her feet.

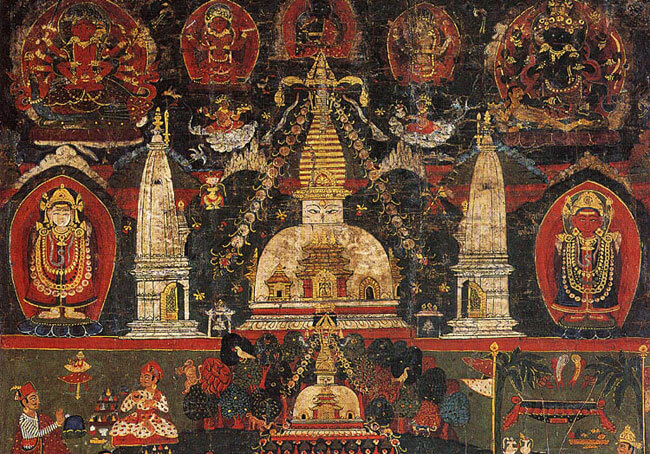

Above, Laksha Caitya. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, The Avery Brundage Collection.1809. Opaque watercolor on cotton cloth.

When, in the midst of this terrifying performance, the Goddess spoke, her voice bayed like the howling of a hundred jackals sending shivers through the viscera of Manjushri’s being. Roaring like thunderclouds and gnashing her teeth, with her eyes bulging and her black tongue projecting horrifyingly from her mouth, the Goddess began to impart her secrets to Manjushri. And Manjushri observed her, as calmly as he could, opening his heart and receiving the divine knowledge into his soul with perfect stillness. After displaying her single-faced form followed by the thousand faces of her most terrifying aspects, the Goddess transformed herself into water and disappeared back into her pitha. This was the ninth day of the waning half of the month of Marga.

On the next day, the tenth of the lunar calendar, Manjushri prepared a suitable conduit for the Goddess’s emissions by covering the opening with a triangular stone slab. In the center was a hole through which the water could safely issue forth.

On the next day, the tenth of the lunar calendar, Manjushri prepared a suitable conduit for the Goddess’s emissions by covering the opening with a triangular stone slab. In the center was a hole through which the water could safely issue forth.

Right, Historic drawing of Swayambhu and its vicinity by Daniel Wright. (From History of Nepal, translated from the Parbatiya by Munshi Shew Shunker Singh and Pandit Shri Gunanand: with an introductory sketch of the country and people of Nepal. Daniel Wright, M.A., M.D., (Editor) Published by University Press, Cambridge, 1877.

Then Manjushri took his principal disciple, a great yogin called Shantikar Acharya, to a deep cave on Sengu Hill and initiated him into the esoteric teaching of the Vairochana and Akshobya cycles and the Chakrasamvara Tantras, just as they had been revealed to him by the Goddess. And so Shantikar Acharya became the valley’s first vajra master, or Vajracharya priest,. And in time, Shantikar Acharya passed on this knowledge to others who, in utmost secrecy and after rigorous training, also became Vajracharya masters, living among the people and using their powers to involve the deities for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Above, Swayambhu Stupa, Kathmandu Valley.

SO NOW THE LOTUS OF SWAYAMBHU WAS EXPOSED ON A HILLOCK WHERE ALL COULD COME AND WORSHIP IT; and around the hillock, where once there had been water, lay a great valley of rich and fertile land. And soon the Valley filled with Manjushri’s disciples, and he designed a glorious city for them in the shape of his sword. He sited this city in a most auspicious place, at the confluence of the Bagmati and Vishnumati rivers fed by the waters that issues from deep inside the Guhyeshvari pitha.

He called the city Manju (sweet) Pattana (city) and enthroned one of his devotees, Dharmakara, as king. And he taught the people who inhabited the city the fundamentals of civilization and people who inhabited the city the fundamentals of civilization and culture, and of farming and husbandry, and also the art of ritual including the Ten Rites of Passage, and devotion to the five Transcendent Buddhas, the Three Jewels and the Ten Perfections, as well as worship of the seven historical Buddhas, and all the attendant bodhisattvas and other gods, and the Astamatrika – the eight mother goddesses, protectoresses of the eight directions. And for those citizens whose dharma it was to live as monks or priests he created monasteries and temples.

Right, The humble house brick made of red clay that epitomises Newari legend and architecture.

He also taught the people of Manjupatta how to venerate the tree spirits in the might forests at the edge of the Valley, so that they might cut down the trees with impunity’ and he showed them how to carve the wood and give it new life. He taught them how to mould and bake the red clay that had once lain at the bottom of the lake so that even the humble house-brick would be blessed and become strong as iron.

They leart how to make roof tiles like the scales of a Naga, with dragon’s head at the roof corners, and to imprint the clay with flowing waves and mythical beasts for cornices in memory of this watery pre-existence; and in no time their craftsmanship was sought after across all the other kingdoms of the Himalaya, and far, far beyond.

Above, a hand-carved wooden torana at Taleju temple entrance.

Above, Devi Taleju Bhawani (with 10 arms standing on a lotus) adorns the Golden Gate in Bhaktapur Darbur Square, Kathmandu Valley. The main entrance to the Kumari temple. Built in 1753 by King Ranjit Malla.

For their own city, they built beautiful, many-tiered pagodas, with dancing deities carved on the roof struts and monasteries with latticed peacock windows, and Buddhas and bodhisattvas in elaborate wooden shields called ‘toranas’ above the doors. Soon they were carving devotional plaques and friezes and reliefs and guardian lions from stone.

Above, Lokeswar Buddha at the Tadhunchen Bahal. Left, A hand-carved wooden torana at Taleju temple entrance. Pages Photos: Heather Elton

Above, Detail of the devotional torana at the Sanku Vajrayogini Temple. Photos on pages 20 & 21 are also taken at Sanku Vajrayogini.

But most magnificent of all was the work they fashioned from gold and silver and bronze. Manjushri taught the people the magical secrets of metallurgy, and from crucibles of molten fire they began to pour and cast images of the gods that were so beautiful they could move heavens. These divinely inspired bronze and goldsmiths became much sought after throughout the world.

But most magnificent of all was the work they fashioned from gold and silver and bronze. Manjushri taught the people the magical secrets of metallurgy, and from crucibles of molten fire they began to pour and cast images of the gods that were so beautiful they could move heavens. These divinely inspired bronze and goldsmiths became much sought after throughout the world.

After he had taught the inhabitants of Manjupattana all these wondrous things, Manjushri made ready to return to his abode on the five-peaked mountain of Wu-tai Shan in China. But before he left, he enshrined an aspect of himself in an image on the western people of the hillock of Swayambhu from where he rains down countless blessings upon the inhabitants of the Valley to this day.

Above, Elaborate wood-carved roof struts at the old Royal Palace in Patan, Kathmandu Valley. Photos: Heather Elton

So pleased were they with all this work of devotion established in the Valley by sweet-voiced Manjushri that from time to time the gods and goddesses themselves would descend from their residences in the Abode of Snows to dwell among the people of Manjupattana and their kings, delighting in the earthly pleasures of the beautiful settlements there and vying for the attention of their illustrious devotees. And in time, Manjupattana came to be known as Kathmandu; the valley, Nepal; and its inhabitants, the Newars. •

‘The Jewel of Beginnings’ is taken from Isabella Tree’s book, The Living Goddess, which is based on the Swayambhu Purana. It is the best account I’ve read of the origins of the Kathmandu Valley.

If this article has sparked your interest in visiting The Kathmandu Valley join Heather Elton’s Yoga Teacher Training in Nepal July 6 – August 4, 2019. Click here for more details and to apply.