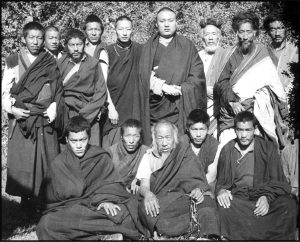

Todgen Yogis, Tashi Jong Gompa & Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche at Deer Park Institute

I’m reading Vicki MacKenzie’s book, A Cave in the Snow, about Tenzin Palmo, the daughter of a fishmonger in London’s Bethnal Green. Palmo came to India in the 60s, was ordained as a Buddhist nun by her guru (the 8th Khamtrul Rinpoche of Tashi Jong monastery) and eventually lived in a remote cave, 13,200 feet in the Himalayas, for 12 years. She slept sitting up in a mediation box for three hours a night and survived temperatures of below – 35 C. with snow seven months of the year. The last three years were spent in complete isolation, until a police inspector rudely knocked on her window and demanded that she leave India as her Visa had expired, breaking her silence. She has become a Buddhist legend and a champion for the rights of women to attain spiritual enlightenment. I read this book about six years ago and was hugely inspired by it, but reading it this time I suddenly realise that all of this happened very close to here. I jump into a taxi and head to Tashi Jong Gompa and Ani Palmo’s nunnery.

When the 8th Khamtrul Rinpoche came to India in the 60s, he brought with him ten elite Himalayan yogis called Todgens (or Tokdens). The lineage dates back to the 17th CE when the 4th Khamtrul Rinpoche started a yogi sangha. Togden means “those who have realisation of the nature of the mind.” Their practices include the Six Yogas of Naropa (inner ‘tummo’ heat, illusory body, clear light, consciousness transference, forceful projection and bardo yoga) and Mahamudra meditation, as well as many other Drukpa Kagyu secret tantric practices. Although they are fully ordained monks, the Todgens keep the matted hair and white robes of the Milarepa tradition.

Today, there are more than 15 yogis from the old and new generations at Tashi Jong. Some are undergoing a profound training that requires many years to complete, and most of them have been in retreat for more than 15 years. They get to wear the yogi’s robes after 12 years of practice, at the completion of their first stage of training. Although they always remain in strict retreat, occasionally they come out to lead monks during important ceremonies.

I arrive at Tashi Jong in hope of catching a glimpse of a yogi. I think ‘where would I be if I were a Todgen’ and follow the path to the very top of the monastery. It’s a sweet place with grand views and flowers everywhere. I arrive at the highest house and inquire about the Togdens and am told to go upstairs. Here is the samadhi of Amtrin, one of the originals who passed away on 1 July 2005 at the age of 84. Apparently, at the time of his death, despite the fact that it was monsoon season, the weather cleared completely for that whole night and the next morning. When a highly realized being dies often their body shrinks in size and peculiar formations are found in the cremation ashes. Sometimes an eye, tongue and heart might remain (corresponding to realised body, speech and mind), as well as an odd assortment of small right turning conch shells, colored pills and gemstones. The mummified relics of Amtrim are exquisitely enshrined in this room surrounded by windows. I do my style of prostration, Surya Namaskar, in his honour and sit. Serenity and warmth fills the room. I feel the energy of the space.

On the way down, I take a remote path and end up in an old section of the monastery with an old house, chorten and prayer flags. Through a fence I see two Todgens, with their long dreads wrapped on top of their heads, eating lunch. I keep hidden as I suspect they are on retreat and wouldn’t want to break their silence. That would be very bad karma indeed! Back in the main gompa, the monks have finished the Long Life puja and I visit the stupa where the 8th Khamtrul Rinpoche was cremated and a Bodhi tree spontaneously grows from inside the structure. Sacred Lama dances (Cham) get underway in the courtyard. The dance ritual was first performed in Tibet more than 300 years ago, was brought to India by the 8th Kamtrul Rinpoche in 1958, and Tashi Jong monks have performed them faithfully ever since it. The dancers wear elaborate brocaded costumes and large masks and dance in highly stylized movements, against the backdrop of the snow-covered Himalayan peaks and the constant beat of drums and rich tones of solemn chants. A Todgen is leading the ceremony.

Late afternoon, I arrive at the Tenzin Palmo’s Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery. It was founded in 2002 to give young women from Tibet and the border regions the opportunity to realize their intellectual and spiritual potential. Her other main intention here is to reinstate the Togdenma (yogini) tradition. Since the Drukpa Kagyu lineage was founded in the 12th century, it has been renowned for its highly accomplished yogis and yoginis, but with the Chinese occupation of Tibet the female lineage has almost died out. I enquire at the office if Tenzin Palmo is around and they say she is and that I can make an appointment with her the following week. I think ‘yes, I’ll definitely drive an hour and a half for tea with a realized being.’

Bir is another Tibetan refugee settlement about 50 km from Dharamsala. It began in 1966, when the highly reputed 3rd Neten Chokling Rinpoche (1928-1973) brought his family and a small entourage to Himachal Pradesh. With the help of foreign aid, he bought over 200 acres of land and established a Tibetan settlement where 300 Tibetan families were given land to build houses. Chokling Rinpoche built the Neten monastery and his disciples formed its first sangha. When he passed away in 1973, his eldest son, Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche (b. 1951), assumed responsibility for completing his father’s vision. The 4th Neten Chokling incarnation was born in 1973, in Bhutan, and was brought to Bir at a young age to be raised by Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche.

The main town of Bir is a bustling filthy little place, with dreadful food, and dogs so dangerous that it’s ill advised to go out at night. (It seems like an appropriate place to study tantra.) But the surrounding landscape is spectacular with colourful homes perched up the mountainside beside a clear running river and overlooking tea plantations, rolling fields of wheat and tsampa (barley) strewn with prayer flags and views of the Himalayas. Bir is also famous for paragliding, as well as being home to a few illustrious Tibetan film directors. Dzongsar Jamyang Khentyse Rinpoche’s first feature film, The Cup (Phörpa) (1999), was based on events that took place here during the 1998 World Cup final. The 4th Neten Chokling Rinpoche is the director of the film Milarepa (2006) and Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche acted in both of them. My purpose in coming to Bir is to visit Deer Park Institute, a center for Classical Indian Wisdom Traditions set up by my teacher, Dzongsar Jamyang Khentyse Rinpoche, as part of Siddhartha’s Intent (http://www.siddharthasintent.org/), that hosts guest lectures and workshops with reputed scholars and mediation teachers. Orygen Tobgyal Rinpoche is teaching an obscure tantric sadhana (practice) and I decide to stay.

Orygen Tobgyal Rinpoche’s teaching is held in the Manjusuri Hall with a giant gilded statue of Manjushuri Buddha (Wisdom). Even against such a magnificent backdrop, Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche (OT) with his inimitable style as a great orator takes center stage. He is powerful and eloquent, with a hint of wrathfulness that makes me think of Manjusuri, himself, wielding the large sword of discernment. His teaching of Chime Phakma Nyingtik ‘Trinle’, or Wisdom Manifestation, is so indescribably beautiful and sweeping in scope and I stop taking notes and am simply awestruck.

This particular teaching is a terma, or treasure teaching, concealed by the 8th CE teacher, Guru Rinpoche, with the intention that it be revealed at specific times in the future. Termas are hidden treasures (texts, relics and transmissions of teachings) concealed by Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) and his consort Yeshe Tsogyal. A terton is a dharma treasure discoverer. Thousands of volumes of the profound, authentic and powerful tantric teachings and material objects have been miraculously found in the earth, water, sky, mountains, rocks and mind by tertons, through the powers of the spirits, non-human beings, and through psychic powers by gifted human beings. By practicing these teachings, many of the followers have attained enlightenment. The Nyingma school has the richest tradition of treasure teachings. Once discovered within the mindstream of realised beings and are transmitted orally to a worthy disciple. Through the terma tradition, Nyingma teachings, transmissions and lineage of enlightened masters have remained unbroken up to this date.

Right away OT tells us that he will not give us the empowerment and we’re lucky, otherwise we’d have an obligation to do the practice. But without the transmission, it’s simply too ephemeral to grasp. A few hours later I see why he made the right decision. Initiations or empowerments are direct transmissions of esoteric wisdom gleaned from the enlightened mind of a Vajra master (tertöns or treasure revealers) to the mind of the disciple. It empowers the student with the meditative techniques for inner transformation, necessary to accomplish the union of bliss and emptiness, and awakens the inherent wisdom and enlightened qualities within us. Since what is being transmitted is not mundane knowledge, but enlightened wisdom that goes beyond our worldly knowledge and language, only a qualified guru with first-hand experience, not a well-versed scholar, can fulfill the task. Apparently, without empowerment, we shouldn’t even hear this teaching. OT says that since Dzongsar Jamyang Khentyse Rinpoche (who owns the teaching) asked him to teach it that he can’t refuse, but that any bad karma ensued will go to DJKR.

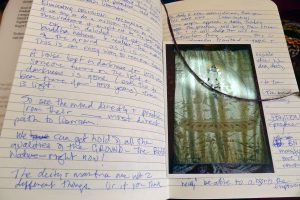

What can I say about this obscure text laced with secret Vajra words, tantric symbolism and so much hidden meaning, that it takes OT 18 hours to explain 12 pages of text, and sometimes 40 minutes to illuminate one Tibetan word? I see why some dharma is considered to be beyond ordinary human thought and why most tantric teachings remain secret. Essentially, like most Vajrayana practices, it generates and dissolves an elaborate visualisation of a deity – in this case, Chime Phakma Nyingtik, who I believe is a form of Tara. It’s like constructing a technicolour, 3-D mandala in the mind where the whole universe is seen as a realm of immaculate purity populated by celestial light beings with indestructible diamond bodies that radiate rays of light in all directions to completely purify everything and all beings everywhere. I love this idea of the ‘formless form’ and supreme beings having intangible, luminous light bodies. Nothing is solid here; all is transparent. The teaching is so infinitesimally detailed, and the spectacular beauty he invokes so elegant and profound that I feel utter awe. I follow his description, image by image, through the sadhana and for a brief moment get a glimpse of what emptiness, primordial wisdom and the Dharmakaya actually looks like. OT’s extraordinary illumination of the text is only possible because he actually practices it. That alone is astonishing.

According to the Buddhist doctrine, Buddhas have three kāyas or bodies: the Nirmānakāya body manifests as solid material forms; the Saṃbhogakāya manifests as luminosity – light and rays – intangible forms only perceivable by those with visionary clarity; and the Dharmakaya, or truth body, is the sphere of unconditioned potentiality and embodies the principle of Buddha Nature’s absence of self, the emptiness of the enlightened mind and transcends the forms of physical and spiritual bodies. According to tradition, those skilled in meditation, such as yogis and highly-realised Tibetan lamas attain this form of clear light upon the reaching the highest dimensions of practice. One manifestation of the Sambhogakaya is that when an enlightened being dies, a transformation occurs into the Rainbow Body leaving behind only hair and nails. The Sambhogakāya body appears in the cosmic realm, or pure land, known as Buddha fields. But what does this have to do with us mere mortals?

At the same time OT invokes the gods, he also brings the teaching back to mundane reality to give practical advice about the practice. He emphatically states that all these incredible qualities belonging to supreme beings exist within us, but we have to actually believe this otherwise it won’t work. We must develop the conviction that now I am who I truly am. He calls it “vajra pride.” He says, “You won’t gain Buddha qualities as a result of the practice. Don’t think that through the practice, you’ll become the deity. That’s lazy! You must become the deity NOW. It’s important to attain the clarity of the visualization, as if something appears in a mirror, but without vajra pride it remains an empty image.” The whole point is to purify our perception and see things as they really are in a state of non-dualism. By practicing in this way, he says that we will very quickly transform ourselves. “The most direct path to liberation is to trust the Rinpoche that this is true, otherwise study sutra and tantra more. Or accumulate a lot of merit and purify obscurations. And, if even this doesn’t work then you don’t have the right karma to proceed on the Mahayana yoga path.”

After the teachings were over, I mention to a couple of friends that I brought two thangkas to Bir to get brocaded. I clearly remember OT saying that for a thangka to be of any use in my practice, it needs to be consecrated. So, they insist that I go to his house and see if he is good to his word. OT lives in a magnificent Tibetan-styled house on landscaped gardens surrounded by high walls. Every single object refers to the dharma and resonates the beauty and devotion of someone with a refined sense of spiritual aesthetic. I feel very small indeed, as I knock on the giant door. The Indian servants let me in but are obviously too afraid to disturb him. In front of me is a large mahogany table with tormas and two fierce lions. I’m definitely not moving beyond it, so sit down to meditate. When I finished the mantra and visualization, OT’s translator appears and I explain why I’m here. He disappears for a moment and then invites me in to meet OT. We unravel the thangkas and he blesses them. Standing behind them, I must have caught the blessing because I was overcome with joy and walked out on a cloud. He smiled at me as I left. He is a man of tremendous presence.