My pilgrimage to Shakti Peeths in the tantric heartland of West Bengal.

By Heather Elton

I arrive in Kolkata and check in to the Ramakrishna Ashram. It’s a delightful little oasis in the otherwise hectic cultural capital of India that is also known as the “City of Joy”. I meet my guide and friend, Kaustubh Das Dehlvi, an Iyengar yoga practitioner and student researching his Ph.D. on Tantra at Calcutta University. His specialty is the wandering Baul musicians and Sahaja yogic practices. I’m blessed that he’s agreed to accompany me on my journey through the tantric heartland. We pour over maps and discuss the itinerary.

On the top of my list of places to visit are the Shakti Peeths in West Bengal. There are 51 scattered throughout India. We have time to visit three of the 13 Shakti Peeths in West Bengal—Kalighat Kali Mandir in Kolkata and Kankali and Bakreshwar in the Birbhum district of West Bengal. I’m disappointed we’re not going to Tarapeeth, infamous for its sacred cremation grounds, home to ash- smeared Aghori yogis who meditate on corpses, drink alcohol from human skulls, and perform other tantric transgressional practices of the left- handed path, and the tantric sadhakas living in huts among the banyan trees that are embellished with red-painted skulls embedded into the mud walls. It’s unclear whether Tarapeeth is an ‘official’ peeth as it is included on some lists, but not others. Tara is also a form of Goddess Kali—Adi Shakti—the divine consort of Shiva. I’ve spent time in the cremation grounds of Pashupati and want to visit the bhaktas of the goddess Tara Ma who feel an intimate connection with her.

I want to see this powerful siddha peeth—a place where yogis can achieve enlightenment or gain supernatural powers, a place that is inextricably bound up with the idea of the cremation ground as a liminal zone. The mahasmashana (great cremation ground) is a tirtha, a place where one crosses over from the physical to the spiritual realm. Or perhaps these two worlds merge. Within this ultimate place of transformation, rituals and sadhana are believed to yield faster and more powerful results.

Tarapeeth is the perfect place to encounter a wild yogini, but Kaustubh Das Dehlvi says it’s too commercial— Disney-fied. Filthy and disgusting. Isn’t that exactly what a charnel ground is supposed to be like? Impure. The place that challenges us to see with pure perception and not allow the mind to become disturbed. Anyway, he promises to take me to more authentic places with fewer tourists in remote parts of Bengal.

In the late afternoon we visit Kalighat Kali Mandir, our first Shakti Peeth. The main form of the Goddess in Bengal is Kali. Kali is one of the fiercest forms of Devi with her wild hair, blood dripping fangs, necklace of severed skulls and the extended tongue sucking up the blood from the battlefield in an act of compassion.

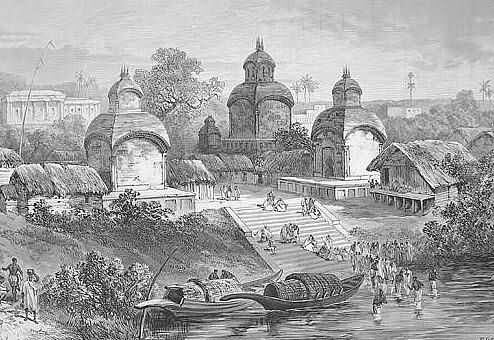

Spiritual transformation is the purpose of pilgrimage and holy places that one visits tend to be situated at tirthas that facilitate this transcendence. Our boat trip across Kolkata’s Hooghly River becomes a symbolic act of spiritual crossing, from the mundane to the sacred abode of the Cosmic Mother— Kalighat Kali Temple. Kalighat is the dwelling place of a particularly fierce incarnation of the goddess, known as Dakshina (south-facing) Kalika. As I approach her riverside dwelling, I imagine the Kalighat of old illustrations, the domed temple rising out of the dense jungle, a remote destination accessed by boat, before it was transformed into a bustling temple complex of one of India’s busiest cities.

Kalighat is a desirable pilgrimage site, perfectly situated to facilitate a shift in perspective from the dual to the non-dual tantric world at the feet of the Goddess. Shiva and Shakti merge here and worship of the Goddess is shared with that of Shiva at the nearby lingam temple. Kalighat is close to the cremation grounds on the banks of the Adi Ganga where people make the final crossing from the realm of the physical to the spiritual. Kalighat is a Shakti Peeth where the toes of Sati’s right foot are said to have fallen, making it the ultimate place of goddess worship where devotees have come for centuries to surrender themselves at the feet of the Divine Mother.

Goddess Dhumavati at Kalighat Kali Mandir is one of the Mahavidyas and represents the fearsome aspect of the Divine Mother. She is often portrayed as an old, ugly widow, and is associated with things considered inauspicious and unattractive. Her ugly form teaches the devotee to look beyond the superficial, to look inward and seek the inner truths of life.

Kalighat temple is 200 years old, but it feels more ancient. Its origins are obscured in myth, but stories about an important Kali temple in this area date to the 12th century C.E. One tells of a devotee who sees a luminous ray of light coming from the river bed and, upon investigation, finds a stone carved in the form of a human toe. He begins to worship Kali in the midst of the thick jungle. Local folklore says that in ancient times, the head-hunting tribal Kapalikas (skull-bearers) who lived here worshiped a dark goddess with human sacrifice. If the origins of Kali worship involved a marginal goddess existing outside of society, in 2020 Kali is very much mainstream.

In the 16th century C.E., King Manasingha built the small hut temple to Goddess Kali that is considered to be the ‘original’ temple of Kali Ma. This shrine grew to its present form thanks to the Sabarna Roy Chowdhury family of Bengal who built the Kalighat Kali temple in 1809 C.E.

The Kalighat Kali mandir is classic Bengali architecture with stacked, hut-like domes that evoke the mud and thatch-roofed huts of the villages. The top dome is crowned with three spires and there is a diamond pattern of green and white tiles cladding the outer walls that remind me of those in a British Victorian pub. Kalighat is a bustling place in one of Kolkata’s oldest neighborhoods. Sadhus sit cross-legged in the adjacent dance hall, counting mantras with their mala (prayer beads), while the usual queue of devotees snakes around the temple complex. I’m escorted past the sacrificial altar whose sticky blood from the Brahmanical sacrifices is a residue of Kali’s tribal roots. I imagine Kali herself would prefer a different kind of blood. Blood from the woundless wound. Menstrual blood. But her connection with ancient rituals of purity and blood-letting endures, even despite her own distaste for slaughter, and in midst of one of India’s most cosmopolitan cities.

Above, Kali Ma at the Kalighat Kali mandir.

The line of devotees moves quickly through the garbha griha (womb chamber, sanctum sanctorum) and soon I’m face to face with Kali Ma. She doesn’t look much like other images of Kali in Bengal. This anthropomorphic deity is sculpted from a monolithic, polished black stone. Three huge eyes, accentuated with brightly-colored orange sindoor (pigment powder), peer out from the garlands of red hibiscus flowers. Her long lolling tongue is made of gold. She holds a curved knife and the severed head of an evil asura (demon)— the scimitar signifies Divine Knowledge and the head represents the destruction of the human ego, which must be slain by Divine Knowledge in order to attain Moksha, or liberation. Her other two hands are in the Abhaya and Varada mudras conveying fearlessness and offering boons. She wears a necklace with 108 cast metal heads of human men.

Darshan with Kali is a sublime experience that leaves me awe-struck, momentarily lost in her beauty that touches my heart; I really feel ‘seen’ by this transcendental deity. I kneel down to touch her feet and surrender my ego and merge with the goddess. A priest breaks my momentary ‘knowing’ and marks my forehead with orange sindoor from Kali’s own body. I am blessed.

Jai Ma!

Another Kali lives here, a magical swayambhu, or self-arisen one. Considered too powerful for the gaze of mortals, she is never displayed to the public, nor is she ever seen by the priests. This is the adi rup (original form) of Kali—one of the toes from Sati’s right foot that fell at this Shakti Peeth—concealed within a box, inside the reclining silver Shiva, upon which the Kalika murti stands. Once a year, a highly secretive ritual takes place behind the sealed doors of the inner sanctum, where blindfolded priests remove Sati’s toe in a full moon ceremony in which it is bathed in Ganga water and scented oils before being freshly dressed and put back into its dwelling place once more.

Kalighat is a place of magic and legend, one haunted by a Goddess that devours all forms of dualism— masculine and feminine, life and death, spiritual and mundane—the Cosmic Mother, an embodiment of all that is nurturing and kind, wisdom and compassion.

Jai Ma!

Above, Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa worshiped Kali Ma at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple.

Just before sunset we arrive at Dakshinwar Kali Temple, the place where Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, the Bengali Tantric mystic and guru to Swami Vivekananda, had his profound spiritual experience with Kali. Ramakrishna (1836 -1886) was a bhakti yogi and had such strong devotion that he actually grew breasts during one of his sadhanas. Like most Tantrikas, he wanted to ‘see’ Kali, have her appear to him, and ‘become’ the deity. On one occasion, he danced all weekend with wild abandon, and took Kali’s curved knife threatening to kill himself unless she appeared. When he tried to cut off his own head Mata Kali appeared to him, grabbed the knife from his hand, and stopped him cold. I want darshan with this Kali that delivered him to enlightenment and whom he took such good care of to the end of his days.

Above, Dakshineswar Kali Temple located in Dakshineswar, close to Kolkata, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River. The presiding deity of the temple is an aspect of Kali named Bhavatarini—She Who Liberates Her Devotees from Samsara (the ocean of existence).

Dakshineswar Kali Temple is a large temple complex, built between 1847 and 1855 C.E., that sprawls over 20 acres on the eastern bank of the Hoogly River. It’s situated on an old Muslim burial ground shaped like a tortoise, considered auspicious for the worship of Shakti according to tantric tradition. The main temple is built in the traditional Navaratna (nine spires) style of Bengal architecture, and rises over 100 feet (30 m) high. It’s cladded in what looks like British Victorian glazed ceramic tiles. It took eight years and 900,000 rupees to complete the construction (paid for by Rani Rashmoni, a philanthropist and a devotee of Kali), until the idol of Goddess Kali was finally installed on May 31, 1855.

Kaustubh has had darshan of Kali many times and knows how to avoid waiting in the queue for over two hours with her regular devotees. We go into a tiny shop where I pay a nominal fee to hire a priest, get puja supplies, and leave my sandals. I’m swept through the temple directly to the garbha griha that houses a manifestation of goddess Kali known as Bhavatarini which means She who Liberates Her Devotees from Samsara (the ocean of existence). She liberates us from suffering and the wheel of karma.

![]()

Above, Goddess Bhavatarini at Dakshineswar Kali Temple.

Despite being escorted by a priest, it’s still difficult to see her. There’s such excitement and devotion here that I feel crushed by the crowd. I’m a female yogini, yet throngs of men are pushing so hard it’s impossible to have darshan. I tell the priest I’m not leaving until I see her. He spreads his arms and pushes the men back like he’s parting the sea, and I fix my dristi (gaze) on her eyes. There she is. Ma Kali Bhavatarini standing on the chest of a supine Shiva, garlanded in sweet smelling flowers and placed on a thousand-petaled lotus made of silver encrusted with glittering, precious, and priceless jewels. I see her wide slanted eyes and long tongue. Darshan is an act of both ‘seeing’ the deity and being ‘seen’ by the deity; a sudden transformation that leads from the ‘outer guru’ to the ‘guru within’ where you can see your own true nature and become one with the deity.

Jai Ma!

At 6 AM we catch the first train to Shantiniketan from Kolkata Howrah Junction. It’s a three-hour journey and I enjoy looking out the windows, sipping chai in clay cups and reading The City of Love written by Kaustubh’s friend, Rimi B. Chatterjee. Our base is a sweet hotel in Shantiniketan, a university town 180 km north of Kolkata.

Above, Chai and Reading on the train. ©Heather Elton.

Shantiniketan began as an ashram in 1863 when Maharshi Devendranath Tagore invited people from all religions to join for meditation and prayers. The spiritual center later became the base for the anti-British reformist Brahmo Samaj movement. In 1921, Devendranath Tagore’s son, Rabindranath Tagore, used the money from the Nobel Prize he received in 1913 (for his book of poems Gitanjali) to build a more formal college which today is known as Visva- Bharati University.

I love the rural, village feel around Shantiniketan. Early morning, the washer men flog clothes on the ghat, in the open air laundromat on the lake. Small goats butt heads under banyan trees. The roads are ablaze with color from flowering trees, bougainvillea petals carpeting the ground. I wander the University grounds, under the mango trees in the open air classrooms of the Patha Bhavana and through the historic buildings of the Kala Bhavana (Institute of Fine Arts) that is famous for the spread of the Bengal School of Art, and boasts an impressive faculty and student body. Mostly, I sit in the Upassana Griha, an exquisite glass house and meditation hall, that Tagore the elder built in 1863. The early morning sun hits the glass and shafts of colored light illuminate the space. The entire place is, indeed, very shanti.

Above, The kund at Kankalitala. ©Heather Elton.

Back at the hotel our driver arrives and we jump in the jeep and head off to our second Shakti Peeth. Kankali | Kankalitala | Kankaleshwari is a temple town on the banks of the Kopai River, 10 km northeast of Bolpur station. Kankali comes from the Bengali word kanal and means “skeleton” because the bones of the Devi fell at this place. Her pelvis/waist fell with such a blow that a kund (pond) appeared in the earth. Adjacent to the kund, is the temple of Devi Parvati. I’m magnetized by the pond and walk the kora (path) around its circumference to sit at the far side. It’s contemplative and beautiful to behold. The reflections on the water seem profound and the colorful floating puja flowers strike an emotional chord. It’s a feminine and peaceful place. Nurturing. Devotees believe that the body parts of the Devi are still here under the pond.

Above, Shrine at Kankalitala ©Heather Elton.

Jaydev Kunduli is the birthplace of the poet Jayadeva, who composed Gita Govinda in Sanskrit in the 12th century C.E. We’re inside the Radha Madhav Mandir (also known as the Temple of Radha Binod) that is rumored to be built on top on Jayadev’s house. Built in 1683 C.E., in the traditional Navaratna style of Bengal architecture the temple has an interesting shape and is ornately decorated with terracotta carvings, representing the ten avatara (incarnations) of Vishnu and scenes from the Ramayana.

Inside the inner sanctum I find Krishna and Radha, the exotic lovers so adored by bhakti yogis. Krishna is black and made from saligram stone, an ancient fossil found in Nepal around Muktinath, a sacred pilgrimage site for Vaishnavites. I’ve been to Muktinath and have a saligram (given to me by my guru) and so having darshan of this murti pulls at my heartstrings. I feel tremendous love for Krishna. Hari OM.

Kenduli is a religious center with many temples and ashrams, but what makes it really special is the Kenduli Mela, or Baul Fair, that attracts several thousand Baul musicians for a month each year, clusters of folk singers who set up camp on the banks of the Ajoy River and sing devotional songs. Bauls have inherited the legacy of the Jayadeva songs. The history of Baul deserves its own article but, in a nutshell, they are wandering minstrel yogis, currently living in Bangladesh and West Bengal, close to villages where they make their money playing songs to the accompaniment of an ektara (a simple one-stringed instrument) and a hand-held drum called a duggi.

Baul music is soulful folk song that celebrates celestial love in very earthy terms. It’s an oral tradition where singer-songwriters pour out their feelings but never write them down. Like most things in the spiritual world, Baul music is becoming more commercial. But in its pure form, Baul minstrels are bhakti yogis who merge their spiritual path with music. Most of them are either Bhakti Hindus or Sufi Muslims and follow Sahaja, an unorthodox devotional tradition that first arose in Bengal in the 8th century C.E. among Buddhist yogis called Sahajiya siddhas. Sahaja means “natural” and, like Buddha Nature, when our true nature is established it brings the state of absolute freedom and peace. Sahaja shares the non- dualist ideas of Tibetan Dzogchen, Hindu bhaktis and the Sufi songs of Kabir. All the lineages have mystic singers, a legacy of song. Baul is an ancient practice that has influenced many kinds of yoga, including the Nath Sampradaya.

Many Bauls are married householders and emulate the divine relationship of Radha and Krishna. Their conjugal relationship is part of their secretive tantric practice and leads to the highest spiritual realization, the state of union or yugala. The element of love, the innovation of the Vaishnava Sahajiya school, is essentially based on the element of yoga in the form of physical and psychological discipline. Amanda Coomaraswamy describes its significance as “the last achievement of all thought” and “a recognition of the identity of spirit and matter, subject and object”, continuing “There is then no sacred or profane, spiritual or sensual, but everything that lives is pure and void.”

One of the classic texts associated with the Sahajiya Buddhists is the Hevajra Tantra. The tantra describes four kinds of Joy (ecstasy):

From joy there is some bliss, from Perfect Joy yet more. From the Joy of Cessation comes a passionless state. The Joy of Sahaja is finality. The first comes by desire for contact, the second by desire for bliss, the third from the passing of passion, and by this means the fourth [Sahaja] is realized. Per- fect Joy is samsara [mystic union]. The Joy of Cessation is nirvana. Then there is a plain Joy between the two. Sahaja is free of them all. For there is neither desire nor absence of desire, nor a middle to be obtained.

We stop at a nearby village called Kalipur to visit Nitai Chandra Das, an internationally-acclaimed Baul musician. Nitai is the third generation of mystic minstrels in his family. We meet him in his ashram at the edge of town, a mud and thatch village hut decorated with musical images.

Nitai Chandra Das sings melodious songs inside his ashram. Jaydev Guru.

Above, Kali Ma at Yogi Baba’s ashram in the Gahr jungle, West Bengal, India.

The Gahr Jungle and Yogi Baba’s ashram is on the opposite side of the Ajoy River. Daniela Bevilacqua (scholar and post-doc researcher on the Hatha Yoga Project at SOAS) mentioned him to me when we met in Kolkata and amazingly our driver knows this yogi well. We drive for about 5 kms on an unpaved road through a thick forest of endless Sal trees, home to Adivasis (tribals), that takes us to the jungle ashram. I have no idea what to expect and my mind is blown.

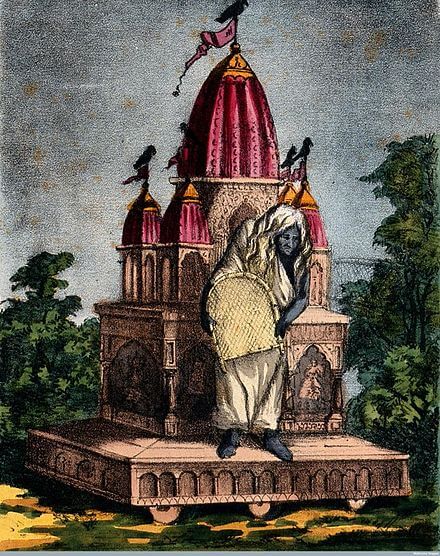

Yogi Baba* is a humble, super fit yogi around 60 years old, filled with vitality, a great sense of humour and sparkling eyes. He is a splendid host, offering us a tour and thali lunch and we are truly blessed to be in his presence. His stomach churning nauli is the best I’ve seen, but this pales in comparison to his other powers. He’s the real deal—a saint, a siddha yogi. He tells us he that he was already a yogi in the womb. As a young child he would slip out of the house at midnight to worship at the Durga temple. He’s a devotee of Devi Durga. In his teens, he mastered every aspect of Patanjali Yoga. He attained sainthood and became Yogi Brahman in the saint Atal Akhara tradition.

Above, *Yogi Baba is worthy of an article dedicated fully to him. If you want to read about his bio in detail and Adivasi stories about his supernatural powers, check out Daniela Bevilacqua’s Old Tools for New Time online. ©Heather Elton.

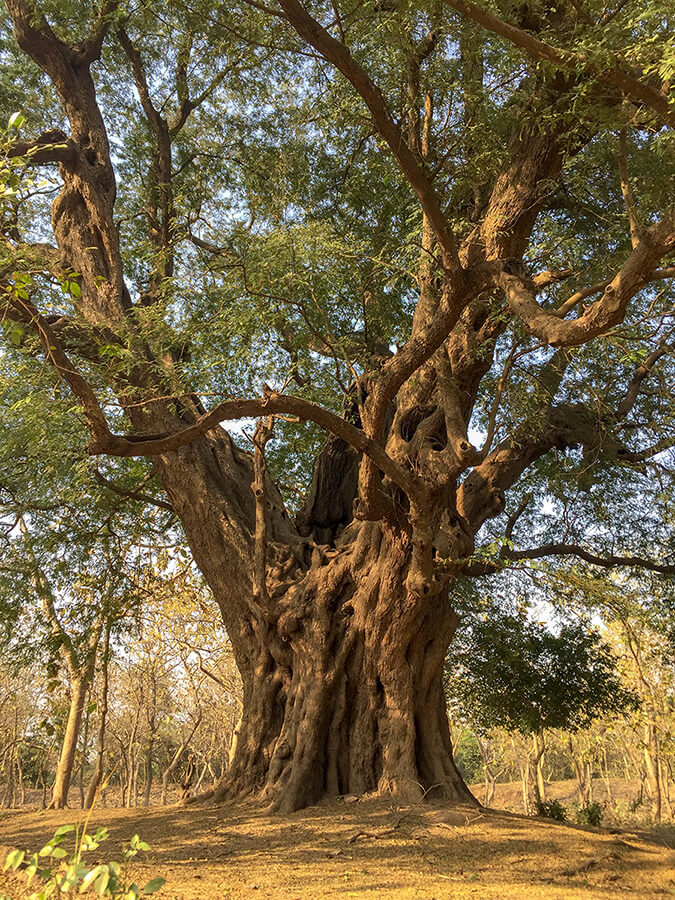

After marriage, a child, and later renunciation, Yogi Baba heard the voice of the Goddess tell him to go to the jungle and to do tapasya there. He spent over two decades in “silent spiritual revolution”, living inside the dense forest where he found a huge tamarind tree and practiced tapasya in its hollow deciding to make it his shelter for the next two years. The more his practice advanced the more his inner vision clarified. He visualized temples hidden in the soil, covered in the jungle, and realized that he was doing his sadhana in an ancient holy place where, during Satya Yuga, the sage Medha had his ashram and where he suggested to King Surath to worship the goddess Durga.

I’m stunned. In my search for the Mother, I actually stumble upon the very place where the first ever Durga Navaratri was celebrated. The place where King Surath met the sage Medha—as narrated in the Devī Mahatmya. I sit down on this ancient land, under a Sal tree which is very, very old with many roots, on the sacred seat of Medha Muni, and through his eyes gaze out across the Ajoy River. I’m lost in time, in a landscape unchanged by modern civilization, totally absorbed in serenity and peace. Jai Ma!

Garh Dham is a tapobhumi, a place where sadhus have attained realization, so any sadhana here will be amplified. Yogi Baba acquired siddhis that now have been told by the Adivasis. Yogi Baba says he “brought back to life” a few small shrines and three main temples from Raja Surath’s time, restoring the place as it was in the past. Even though many forms of Devi Durga were revealed in the Devi Mahatmya, the temples here are dedicated to Maha Kali, Maha Lakshmi and Maha Saraswati.

Above, Ancient samadhis at Bakreshwar.

Bakreshwar is renowned both as a place of power for goddess worship and for the Shiva temple devoted to the crippled sage Ashtavakra. Sati’s third eye fell here, or at least the place between her eyebrows. Adi Shakti is commemorated at this powerful Shakti Peeth in a temple dedicated to the form of Devi Durga as Mahishamardini Bhairavi. At the heart of Bakreshwar, the spiritual traditions of Shiva and Shakti merge, creating the perfect place for tantric practice.

Bakreshwar is also known for its scenic beauty and as a legendary place of healing. The Phaphra river is said to be the Remover of Sins and the sage Mahamuni Ashtavakra found enlightenment here after submerging himself in the water. People suffering from all kinds of ailments come here, seeking physical respite in the therapeutic hot springs and divine grace through the temples.

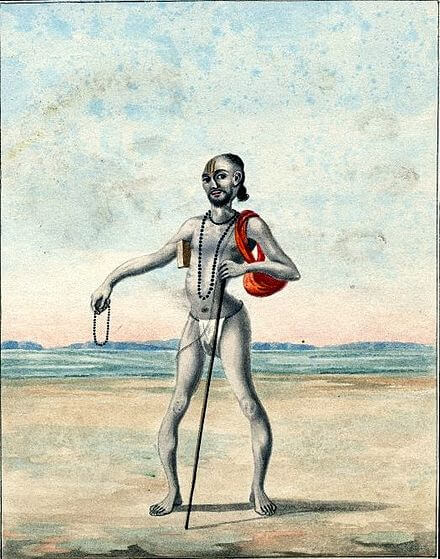

Above, Mahamuni Ashtavakra.

The name Bakreshwar is a compound of two words: vakra, meaning “curve” or “deformity”, and ishwar meaning “lord”. According to local legend, during the time of Satya Yuga, two munis, or sages, were invited to the marriage ceremony of Lakshmi and Narayana. When Rishi Lomas was received first, Rishi Subrita was ferocious with anger, so tormented that the emotion twisted his body into eight curves, hence the name of Ashtavakra. Disfigured and disillusioned, he decided to perform penance for his sin— sages weren’t supposed to succumb to destructive emotions like anger—and went to Varanasi to pray to Lord Shiva. He heard a voice telling him to travel to a place called Gupt Kashi. The crippled sage eventually landed in Bakreshwar where he did tapasya and meditated upon Lord Shiva for 10,000 years. Profoundly moved by his dedication and penance, Shiva blessed Ashtavakra Muni at Bakreshwar. He not only cured his beloved devotee of physical deformity, but declared that those who visit Bakreshwar and venerate Ashtavakra will be graced with a surplus of boons.

Bakreshwar was on my radar because my Guru was here with his Guru, the famous Yogiraj Dr. Ramnath Aghori. It’s a legendary place where siddhas and yogins extracted mercury from the geothermal waters for alchemical purposes. Pure medieval tantric yogi science.

Above, Ancient samadhis at Bakreshwar.

Crumbling lingam mandirs are scattered throughout an ancient graveyard. Banyan trees embrace the small hut-like structures made of concrete, their roots a witness to time. These tombs, or samadhis, mark the graves of saints buried sitting upright in padmasana (crossed-legged lotus posture)—spiritual adepts, Tantriks, and mystics. Small pathways lead to numerous ashrams where yogis still live and down to the cremation ground on the banks of the Phaphra River. Bakreshwar is an auspicious place to be cremated and so there is an ample supply of skulls and bones for Aghori yogis. It still has a medieval feel, as if frozen in time; the dreadlocked sadhus could be Nath Siddhas, ancestors of Gorakshanath or Matsyendranath, medieval yogi scientists concerned with immortality and transcendence of the human condition. It’s a perfect little yogi town in the middle of nowhere.

We walk up a narrow street lined with wooden stalls selling puja supplies and kitsch souvenirs. The Bakreshwar Temple comes into view with its distinctive shikhara (rising tower above the inner sanctum), an architectural style that is more Orissan than typical Bengali. I ring the assortment of brass bells in the tunnel-like corridor leading to the main temples, and hear them echoing into silence as I sit on the steps of the kund to dangle my feet in the mineral-rich water. Some people swim here. There are several hot springs—Agni Kund, Brahma Kund, Surya Kund, Saubhagya Kund, Amrita Kund, Kheer Kund, Jibat Kund and Vairav Kund. I smell the sulfurous water and wonder about the alchemical practices of Aghori yogis.

Mercury. What does a yogi do with this mysterious substance? The Rasa Siddhas, the alchemists of medieval India, had an expression: “…as in metal, so in the body”. But what does this mean? We know what happens to certain minerals when they come in contact with others and are heated; a transformation from solid to gaseous states can occur. Is this a metaphor for Tantra and the subtle energy body practices of Kashmiri Shaiva and Kaula schools of yoga? Is it an ancient aphrodisiac, or a tantric visualization to transform the elements in the chakras from earth to ether? Is it an elixir where human sexual fluids mix with divine mineral substances in the ultimate consummation of love?

Perhaps there is evidence in the landscape. In his book, The Alchemical Body, David Gordon White talks about alchemical places in India that are worshiped as Shiva and Shakti. Bakreshwar is one of these revered sites—a mineral manifestation of Shiva and Shakti. Her sulfurous waters contain mica and sulfur, emissions from the Goddess. Mica is her ‘seed’, or sexual emission, and sulfur her uterine or menstrual blood. Mercury is the shining liquid, the volatile semen of the phallic god Shiva. The mercurial springs and sulfurous waters of Bakreshwar merge to heal devotees.

Yogis swallowed mercury to become a second Shiva, an immortal Siddha. “Until such time when one eats Shiva’s seed, that is, mercury, where is his liberation, where is the maintenance of his body?” Mercury has to do with the path to ecstasy and the divine, and the transformation of mortal, aging man into a perfected, immortal being.

Above, Offerings on a banyan tree at Bakreshwar.

Purified. I enter the garbha griha of the Vakranath Temple that houses the lingams associated with Shiva and the sage Ashtavakra. The small room is tiled in white ceramic and has a marble floor. In the center is a yoni (vagina, symbol of creation) made of brass-like metal set more than a foot below the floor. Situated in the yoni is the sacred lingam of Ashtavakra—made from eight symbolic metals: gold, silver, copper, zinc, lead, tin, iron, and mercury. The priest performs puja and makes offerings of marigold flowers and bael leaves, libations of water and milk, as well as incense and candles which are lit and placed around the yoni. There is also a secret second lingam nestled inside the yoni, toward the base of the Ashtavakra lingam. I touch a smooth, round stone that feels slippery in the darkness.

Between the Shiva temple and the goddess temple is a sacrificial altar in the shape of a wooden fork, painted bright red, the colour of shakti– feminine power. The orange shikhara of the Mahishamardini Mandir towers above. I push open the wooden doors with hand-carved friezes of Lakshmi, Saraswati, Ganesha and Kartik, and the three-fold symbol called ghatam, meaning “pot”. Devi Durga is inside, an ashtadhatu murti—made from an alloy of eight metals that have astrological significance. She has ten arms, is accompanied by her lion vahana (animal vehicle), and is thrusting a spear through the heart of the demon Mahisha. Other than the spear, Durga is without her usual assortment of weapons. Holes in the nine remaining fists allow devotees to add a personal touch to their puja by placing a miniature tin weapon— available in the nearby shops—in one of her hands as an offering.

I give the priest a traditional offering of incense, flowers, sindoor (red pigment powder), decorative bangles and fruit for the Goddess at this precious Shakti Peeth. He draws my attention to a circular hole on the marble pedestal beneath Durga. I place my hand inside the hole to touch the original form of the Goddess, her bhru moddo, or the space between her eyebrows, symbolic of her mind. It feels smooth and cool and sliding my fingers along the surface, I can make out the shape of a lunar crescent with rounded edges. I feel a shudder ripple through my spine as I touch her third eye, her Ajna Chakra, as I merge with the vastness of her goddess mind. I feel her transcendent beauty inside me and time stands still. I feel blessed and absorb the tangible power manifested over the centuries, through this humble embodiment of the divine.

Above, Devi Durga in the Mahishamardini Mandir at Bakreshwar.

The cremation ground is at the end of a narrow, unpaved road flanked with tombstones that rise up like jagged teeth. Shiva devotees prefer the custom of cremation but Vishnu worshipers like to be buried. Both traditions are evident at Bakreshwar. Near the entrance to the cremation ground is a small temple to Kali. “Jai Ma Smashana Kali” (“Victory to Mother Kali of the Cremation Ground”) is written above its door in bright red Bengali script.

Inside is a murti of Kali standing on her husband, Lord Siva, with her left foot pressed against his heart, bran- dishing a sword and holding a severed head with her left hands while her right hands give the mudras of Abhaya (fear not) and Varada (conferring boons). She is depicted as the archetypal dark moth- er goddess, with a few macabre embel- lishments to emphasize the particularly fierce nature of her smashana (cremation ground) aspect. Painted red lines flow from the corners of her mouth down her neck to suggest oozing blood. Two semi-nude female shaktis (human em- bodiments of transcendental feminine force) are depicted in a frenzied dance, smeared with entrails and feasting on human flesh.

Bakreshwar’s sacred burning ground might appear unceremonious compared to Tirupati, Pashupati or Varanasi, yet it’s auspicious to be cremated here and people come from as far away as Bihar. The Dom cast have their work cut out for them today as four cittas (funeral pyres) are burning on scorched earth, permeated with ash, beside the black water of the Phaphra river. They tend the fires and break down the bodies that are slowly turned to ash.

I don’t see any Aghoris propitiating Chamundi with blood, meat and alcohol offerings, or dakinis wearing bone ornaments, but the Dom are hospitable and offer us chai and crackers, as they smoke bidis (tobacco- leaf wrapped cigarettes) and ganja, and drink bangla, the local rice-based moonshine. It seems appropriate that this marginalized caste, thought to be filthy ‘untouchables’ by the nature of their work, would venerate a low-caste female as the ideal cosmic matriarch. Kali the Mother is a multifaceted deity who undoubtedly developed through the synthesis of indigenous goddesses whose roots reach back into prehistory.

Jai Ma!

It’s a grey, ash-sodden kind of day. We cross the murky Phaphra, known as the Remover of Sins. Ashtavakra Muni is said to have found enlightenment here after bathing in the waters. That was during the Satya Yuga, not the Kali Yuga, and today my pure vision fails me. I step on sandbags and try to avoid the water as we cross the sacred river to visit the goddess temple on the other side.

Above, Small Durga shrine in the jungle at Bakreshwar.

Spiritual transformation is the purpose of pilgrimage. My own journey has been one of embracing the Mother. I traveled as a yogini, a devotee and practitioner, to holy places situated at tirthas (crossings) or peeths (seats of the divine), not as a spiritual tourist, but as a ‘seer’. Each auspicious place I visited felt not only alive, but expansive like an energetic vortex that drew me to unknown depths allowing me deeper access to myself and other realms. It was easier to communicate with the divine and receive her blessing.

I left the earthly realm of Calcutta, crossing the waters of the Hoogly River to the spiritual abode of Kalighat, travelled through the contours of the West Bengal landscape that resemble the body of the goddess, and sat at peeths where parts of her body fell to earth. I now understand sacred symbols like wa- ter pots, garlands of red hibiscus, orange and red marigolds, anthropomorphic stones, triangular openings painted red, stone yonis and lingams. I tried to embody her with all my senses. I gazed into the eyes of the deity (darshan), touched her with my hands (sparsa), heard the sacred sound vibrations of mantras and the ringing of bells. I smelled the incense and flowers, ate the consecrat- ed food, sipped the sanctified liquid

offerings. I traveled through time and history to grasp her vast terrain, from the goddess as creatrix in sacred texts, to the pre-Vedic yakshis, tantric yoginis, to Durga with her lion mount, and emblems and mudras indicating her various powers and her many manifestations. My journey strangely led me to the very place where the Devi Mahatmya was first uttered by a Vedic sage, knowledge ‘seen’ in a vision by Yogi Babi himself. I’m no longer confused by the many different names and forms of the Devi— her nama rupa—and under- stand that her different aspects connect to ones within me. I made a connection from the macrocosm to the microcosm. Each of her forms describes the visible, changing world of samsara and the multiple worlds of the gods. To determine what is real and what is a dream.

For me, the most direct route to the heart of the Mother, and by extension to my own heart, is through darshan. Darshan with the murti, or sculpture, in which the deity has taken form, is an intimate and profound form of worship. The presence of the eyes of Hindu divine images are a reminder that it’s not only the worshiper who ‘sees’ the deity, but the deity ‘sees’ the devotee as well. When eye contact is exchanged, the true inner nature of the devotee is revealed. The Guru lies within. Darshan with Kali was a sublime experience and her anthropomorphic beauty touched my heart. I really feel ‘seen.’ Her divine gaze realized my own feminine nature and I saw myself.

Darshan can also mean a mystical or visionary experience and is used to describe the Darshanas, or systems of Indian philosophical thought. Darshan is a point of view. What I now ‘see,’ or know, is that Devi is in everything. Every rock, creature and physical structure is imbued with Sakti. Each is an integral part of an enchanted world where the profane and the sacred merge. I deepen my commitment to a non-dualist view of the world.

Embracing the Mother hasn’t come naturally to me. As an adopted person, the concept of mother and my own relationship with my mother(s) has often been fraught, but since traveling through the heartland of Bengal to the Shakti Peeths—her toe at Kalighat, pelvis at Kankali and eyebrows at Bakeshwar—and asking for her blessing, I find that my own relationships have become easier. Graciously accepting the sindoor from Kali’s body, I’m more able to receive. The Mother teaches us to appreciate our own afflicted emotions as substances to work with and transform back into the unconditioned, unfabricated state of mind. I felt myself melt into emptiness with the awareness that this suchness is pure consciousness. Going beyond the space/time continuum into more subtle realms between form and formlessness. Mother offers a glimpse into Moksha (liberation) and, ultimately, my own true nature. I’m able to accept love and truly see the Mother as a com- passionate being.

In my investigation into various forms of Durga, I feel drawn to her darker and more wrathful manifesta- tions of Kali, and Chamundi, associated with the charnel grounds. They have taught me to embrace my own shadow and wild nature. Thanks to her I can now embrace my own feminine and gracefully move forward towards my crone-like demise.

I’ve been looking for a special deity for Nyasa practice and, suddenly, Ardhanarisvara, the Half-Female Half-Male God manifests. This deity is half Siva and half Shakti, a gender fluid and androgynous deity split down the middle: one breasted, clothed half in female yogini garments and half in male tantric yogi attire. Sometimes Shiva and Parvati are joined, as are Vajrayogini and a manifestation of Padmasambhava. In the true non-static, ever changing state of the Devi, everything is in a state of motion and vibration. All the goddesses come to visit me. They teach me to be fearless and compassionate. Compassion for all sentient beings.

Jai Ma!

Heather Elton is a yogini, writer and photographer living in London.

The article was originally published in Namarupa magazine.

Namarupa, Categories of Indian Thought, is a journal that seeks to record, illustrate, honor, as well as comment on the many systems of knowledge, practical and theoretical, that have originated in India. Passed down through the ages, these systems have left tracks, paths already traveled, which can guide us back to the Self — the source of all names [NAMA] and forms [RUPA]. NAMARUPA presents articles that shed light on the incredible array of DARSHANAS, YOGAS and VIDYAS that have evolved over thousands of years in India’s creatively spiritual minds and hearts.